One day, after a few hours of fighting in which the Taliban had not yet hit any Marines, a corporal from Second Platoon stood upright, exposing himself above the waist and looking over a wall as bullets flew high overhead. He didn’t flinch. “What’s everybody ducking for?” he said. He cupped his hand to his mouth and shouted an expletive-laden taunt at the Taliban gunmen shooting from concealment on the opposite side of a field. The editors would never allow the corporal’s words to be printed here. But they amounted to this: You guys can’t shoot.

*****

Thanks to Doug for bringing this to my attention. Man, did the Italian Carabinieri just show up the DynCorp police instructors or what? lol Training folks requires patience and a profound understanding of the fundamentals. Good on the Italians for correcting the issue. But it also highlights the importance of standardizing this contract, so you don’t have companies or even the military doing whatever they want.

I cut that one little piece of reportage out of this first article posted below, just to get the ball rolling for this post. Marksmanship is something contractors are teaching to Afghans, Iraqis, Ugandans, Nepalese, you name it, and there are so many issues that come up when trying to teach this life saving and essential skill to the troops. For this post, I will highlight the Afghan issues and present the six points that Mr. Chiver’s mentioned in his excellent reportage on this topic. I am not saying these apply to all forces being trained, but for Afghanistan, this is what has been identified. So with that said, let’s get started.

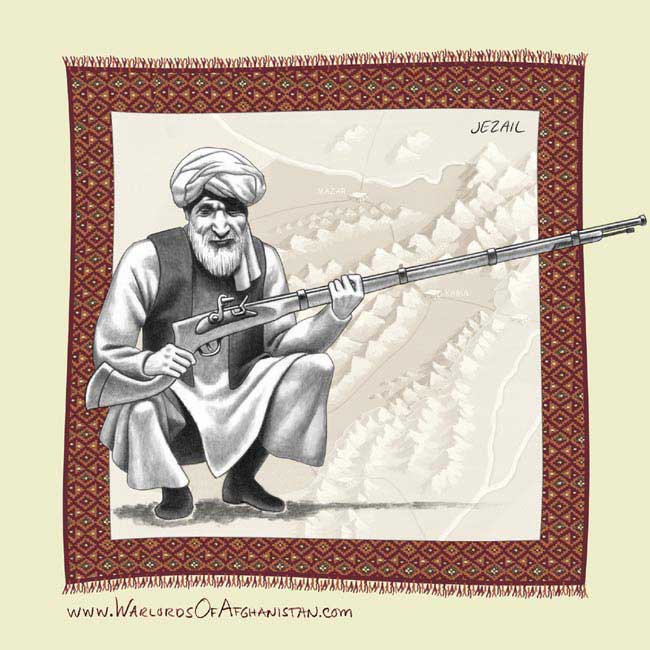

In a prior post, I mentioned the concept of the Jezailchis Scouts (JS). Or basically create a scout/sniper force in Afghanistan that would pride itself as being the premier Afghan tracking and killing/capture force. Something along the lines as the Selous Scouts. A force that all Afghans would look up to and highly respect. This force would be the go to guys for hunting humans up in the mountains, and they would have great utility (pseudo operations, sniper operations, scouting, snatch and grab, etc.). Marksmanship and the ability to track and survive on their own, would be the hallmarks of this crew. It would also draw from that fabled history of the Afghan being a good marksman, hence the Jezailchi reference in the name of the group.

But as the reader will find out, Afghans on both sides of the conflict, suck at marksmanship. Mr. Chivers boiled it down to the six areas that are contributing factors to poor marksmanship on the side of the Taliban (but could easily apply to Afghan Army or Police forces)

Here they are.

1. Limited knowledge of marksmanship fundamentals.

2. A frequent reliance on automatic fire from assault rifles.

3. The poor condition of many of those rifles.

4. Old and mismatched ammunition that is also in poor condition.

5. Widespread eye problems and uncorrected vision.

6. Difficulties faced by a scattered force in organizing quality training.

The second Chiver’s article also mentioned what happens when a enemy force can’t shoot–they adapt. In this case, AK 47’s were used to cause reactions in patrols. Meaning, if an ambushing force fires the weapons and the patrol of Marines runs to the closest protection that happens to be pre-rigged with IED’s, then that ambushing force could command detonate and kill the Marines that way. So the enemy knows it sucks when it comes to shooting, so they just use the weapon as a catalyst to get our forces into traps or to delay our forces. Nothing new, and this is a tactic used over and over again in the history of warfare.

But going back to the marksmanship thing, I personally think that this is a weakness that would should be exploiting. We exploit it by creating some good ol fashion kick ass Afghan shooters, coupled with Coalition snipers and marksmanship mentors. We also have the coalition bring in weapon systems that can reach out and touch someone, and has optics. I continue to read reports that this last part is happening, and that is good. We should be picking these guys off from across the canyons or at distances that the Taliban cannot engage at.

That brings up the other point of the article. The two weapons systems that the Taliban are able to actually hit people with, are the PKMs and sniper rifles (with trained snipers using them). The PKMs makes sense, because a machine gunner can adjust fire easily, and concentrate fire better and at distance. It is the only weapon system that suits the capabilities and limitations of the kind of fighters using it. (please refer to the six points up top)

Now for the Afghan Army and Police, there are a few things we could do to bring them up to speed quickly. Giving them eyeglasses would be a start. lol Also, some accountability must be shown for the quality and functionality of all weapons and ammo issued.

Some ideas off the top of my head would be to modify the AK or the issued M-16 to only shoot semi-auto. It would force these guys to shoot one shot at a time, as opposed to the spray and pray technique. The other thing that could be done, is to put reflex sites on these weapons–stuff that is AK tough and does not require batteries. That way, you have a weapon that is Fisher Price simple for the Afghans to use, and they won’t be able to use it like a fire hose. If the weapon is better suited to the user, then the other aspect of teaching marksmanship fundamentals will go a lot easier. There should also be an effort to cull the best of the best from these groups, and get them in marksmanship focused group like the JS or whatever special forces that has been created.

Finally, marksmanship could be promoted in Afghan society once again. Competitions could be held, cash or goats could be issued as prizes, and competent Afghan shooters could be identified and approached for recruitment into the JS or Army. Hunters could be rewarded for meat collected, or hide or whatever, and they could be approached as well. Hunters throughout the world are all the same, and I am sure there are plenty in Afghanistan who are very good at it and enjoy the sport. You just have to develop an outlet to attract these guys. Even in the Army and Police, I am sure there are those who could really shine with marksmanship if they had an outlet for such a thing. Especially if marksmanship billets paid more–you would definitely increase the interest in such a thing. Stuff to think about, and thanks to Mr. Chivers for some excellent information on the matter. –Matt

Edit: 04/11/2020 Here is the next article Mr. Chivers wrote about Afghan Army and Police marksmanship. Awesome.

——————————————————————

The Gang That Couldn’t Shoot Straight

Six billion dollars later, the Afghan National Police can’t begin to do their jobs right—never mind relieve American forces.

By T. Christian Miller, Mark Hosenball, and Ron Moreau

Mar 29, 2010

(Only a portion of the article is posted, and follow the link to read the entire thing)

At Kabul’s police training center, a team of 35 Italian carabinieri recently arrived to supplement DynCorp’s efforts. Before the Italians showed up at the end of January for a one-year tour, the recruits were posting miserable scores on the firing range. But the Italians soon discovered that poor marksmanship wasn’t the only reason: the sights of the AK-47 and M-16 rifles the recruits were using were badly out of line. “We zeroed all their weapons,” says Lt. Rolando Tommasini. “It’s a very important thing, but no one had done this in the past. I don’t know why.”

The Italians also had a different way of teaching the recruits to shoot. DynCorp’s instructors started their firearms training with 20-round clips at 50 meters; the recruits couldn’t be sure at first if they were even hitting the target. Instead the carabinieri started them off with just three bullets each and a target only seven meters away. The recruits would shoot, check the target, and be issued three more rounds. When they began gaining confidence, the distance was gradually increased to 15, then 30, and then 50 meters. On a recent day on the firing range only one of 73 recruits failed the shooting test. The Italians say that’s a huge improvement…..

Story here.

—————————————————————–

Afghan Marksmen — Forget the Fables

By C.J. CHIVERS

March 26, 2010

The recent Marine operations in and near Marja brought into sharp relief a fact that contradicts much of what people think they know about the Afghan war. It is this: Forget the fables. The current ranks of Afghan fighters are crowded with poor marksmen.

This simple statement is at odds with an oft-repeated legend of modern conflict, in which Afghan men are described, in clichés and accounts from yesteryear, as natural gunmen and accomplished shots. Everyone who has even faintly followed the history of war in Central Asia has heard the tales of Afghan men whose familiarity with firearms is such a part of their life experience that they can pick up most any weapon and immediately put it to effective work. The most exaggerated accounts are cartoonish, including tales of Afghan riflemen whose bullets can strike a lone sapling (I’ve even heard “blade of grass”) a hilltop away.Without getting into an argument with the ghost of Rudyard Kipling, who was one of the early voices popularizing the wonders of Afghan riflery, an update is in order. This is because the sum of these descriptions does not match what is commonly observed in firefights today. These days, the opposite is more often the case. Poor marksmanship, even abysmally poor marksmanship, is a consistent trait among Afghan men. The description applies to Taliban and Afghan government units alike.

Over the years that Tyler Hicks and I have worked in Afghanistan’s remote and hostile corners, we have been alongside Afghan, American and European infantrymen in many firefights and ambushes. These fights have involved a wide set of tactical circumstances, ranges, elevations, and light and weather conditions. Some skirmishes were brief and simple. Others were long and complex, involving as many as a few hundred fighters on both sides. One result has been consistent. We have almost always observed that a large proportion of Afghan fire, both incoming and outgoing, is undisciplined and errant, often wildly so. Afghans, like most anyone else with a modicum of exposure to infantry weapons, might be able to figure out how to make any firearm fire. But hitting what they are aiming at, assuming they are aiming at all? That’s another matter.

There are exceptions. The Taliban snipers in Marja were one recent example. We will revisit them here soon. Now and then a disciplined Afghan soldier or police officer also bucks the trend. Credible accounts of Northern Alliance fighters in the 1990s and early 2000s chronicled impressive shooting skills among seasoned Panjshiris. But the larger pattern is firmly established and consistent with the experience and observations of countless soldiers and Marines we have passed time with, including many people who have trained and fought beside Afghan security forces during the past decade.

Today At War will share a few observations about inaccurate Taliban rifle fire. Naturally, this will deal with what can be assessed of incoming fire; we do not embed with Taliban units and thus we have no chance of an unfiltered side-by-side look at their marksmanship habits. (Watching videos that the Taliban and their sympathizers post on the Internet or circulate in bazaars has its limits; these are self-selected excerpts chosen in part to show Taliban prowess. Taking them at face value would be much like trying to measure the American Army’s performance in the field by watching a recruiting ad, or like sitting through some of the cheery PowerPoint presentations that officials in capitals serve up for visitors.) The next post in the series will discuss several factors that contribute to poor Taliban marksmanship. A post soon thereafter will address the shooting skills and habits of Afghan soldiers and police officers. That third post will cover more fully what can be seen of outgoing fire, accounts that are possible because Afghan government shooting is readily observable, at least for those who log enough weeks in rural firebases or on patrol.

Let’s start with a few rough numbers. During the month and a half we spent in Helmand Province, Tyler and I combined firsthand observations with queries to officers commanding Marine rifle companies we worked beside. Three of these companies had been engaged in what, by the standards of the Afghan war, was heavy fighting. Here is what their experiences turned up.

Before the full offensive into Marja began, the Marine ground unit engaged in the most regular fighting with the area’s Taliban was Bravo Company, First Battalion, Third Marines. The company served for a little more than two months on what Marines call the “forward line of troops.” In this capacity, it rotated platoons through positions several miles to Marja’s east, a pair of lonely outposts on the steppe overlooking Route Olympia, which was the road leading into Taliban turf. The Taliban had an interest in watching for American movement along this road, and the Marines patrolled constantly near it. Thus the tactical climate was violent and busy. The insurgents harassed the outposts and frequently skirmished with Marine patrols.

In this contest, the Taliban also had the sort of local advantages common in guerrilla war. They knew the network of irrigation canals and used them as trench lines. They littered the fields and small terrain features with hidden bombs rigged to pressure plates. They deployed spotters with radios on motorcycle patrols, which tried to find the Marines and relay word of their movements and activities. They also chose when to fight, and often opened fire on the Marines in the late afternoon, when the sun was low in the sky. Why? Because Marine patrols originated to the Taliban’s east, and as the Marines walked generally westward across the flat steppe toward the area where the Taliban hid, the Marines were walking into the angled sunlight, which illuminated them perfectly for the Taliban, but forced the Marines to look into hard light, and squint. This was an environment in which small-arms clashes were almost inevitable, and in which the Taliban would often get to fire the opening shots. It should have been a place where the Taliban might succeed. What did the numbers show? By early February, when Marine units began massing for the push on Marja, Capt. Thomas Grace, Bravo Company’s commander, estimated that his platoons had been in at least two dozen firefights, often in open terrain. Some of the fights lasted several hours. At least one lasted a full day and into the night. How many of the company’s Marines and the Afghan soldiers who accompanied them had been shot? Zero.

Farther west along Route Olympia is an intersection known as Five Points, so named because several dirt roads meet there. The juncture provides access to northern Marja. Marine Expeditionary Brigade-Afghanistan, the command that planned the attack on Marja, deemed this essential terrain for securing the region. In January, another unit — Charlie Company, First Battalion, Third Marines – was assigned to fly in by helicopter and seize and hold the intersection. This happened in February, a few days before the larger assault began. It prompted a determined Taliban response.

Once the Taliban realized the Marines had leapt by air over their outer defenses, they clustered near Five Points and fought Charlie Company intensely, especially in the first few days. During this time, according to the company commander, Capt. Stephan P. Karabin II, his Marines were in about 15 firefights. Again the Taliban had certain advantages. They knew the ground well enough that their fighters stashed small motorcycles in canals that had been drained. After ambushing the Marines, they sometimes dropped into a dry canal, ran through the maze, jumped on their bikes, started the engines and blasted away at speeds that no one pursuing on foot could hope to match. Smart tactics. But the Taliban did not always run. They often held their ground and fought, perhaps feeling protected by the canals that did contain water, which typically separated them from the Marine patrols they chose to fire upon.

To change the character of the fighting, Captain Karabin ordered his Marines to patrol on foot with their .50-caliber machine guns. These would be lugged along in pieces, and when a firefight began, the Marines assigned to them would put them together, mount the weapons on their tripods, load belts of ammunition and open fire. (A M2 Browning machine gun and tripod weighs nearly 130 pounds; this does not include the weight of the ammunition.) The heavy guns tilted the fighting more fully in the Marines’ favor. But the fact that M2s were used this way said something about how the Taliban fought; some of this fighting was pitched. How many of Charlie Company’s Marines were struck by Taliban bullets in these engagements? Once again, none.

Neither of these companies was spared casualties. Four separate bomb blasts killed two Marines from Bravo Company and wounded nine Marines from Charlie Company. But the Taliban’s rifles were another story. Together the two companies were in about 40 firefights against the main guerrilla force in a nation that is considered, by the conventional wisdom, to be a land of born marksmen. And not a single bullet fired by the Taliban found its mark.

Obviously, American and Afghan soldiers do get shot, which brings us to the third Marine company, which suffered the effects of more accurate fire. As Charlie Company was fighting at Five Points, Kilo Company, Third Battalion, Sixth Marines, was inserted at night by helicopter into three landing zones in northern Marja, where it was soon met by what may have been the stiffest Taliban resistance of the offensive. For nearly 10 days, Kilo Company was engaged in small-arms fighting. In the first four or five days, the fighting was widespread, often with several firefights occurring simultaneously as different patrols and different platoons on different missions were locked up in skirmishes at once. On the second day of fighting, one skirmish alone, between two platoons and large groups of Taliban fighters, lasted off and on from early morning until night.

Within a week or 10 days, eight of the company’s Marines had been shot, two fatally, and two Afghan soldiers had been shot as well, including one who died. This is a large number compared with the experiences of the other two companies, but it is a small number when set against Kilo Company’s size, and when considered in the context and the volume of Taliban fire.

First, about the size. In all, Kilo Company had on the order of 300 men assigned to it, including engineers, dog handlers, bomb disposal and intelligence specialists, interpreters and an Afghan infantry platoon. (Note: Embed rules forbid precise descriptions of unit and team sizes, so the numbers of the various units that made up Kilo Company on this mission are mashed together here and rounded.)

Now the context. On many days, Kilo Company’s patrols would be ambushed while crossing flat, open ground, with no vegetation concealing the Marines’ movements and no place to take cover without running a couple of hundred yards or more. Often many Taliban gunmen would open fire simultaneously, and a large number of rounds would fly into the area where the patrol walked. Rounds would snap and buzz past helmets. Rounds would thump all around in the dirt. But usually no one would be struck. It happened again and again.

When Marines did get hit, it often appeared that the fire came from PK machine guns or the local contingent of snipers – not the riflemen who make the Taliban’s rank-and-file. One day, after a few hours of fighting in which the Taliban had not yet hit any Marines, a corporal from Second Platoon stood upright, exposing himself above the waist and looking over a wall as bullets flew high overhead. He didn’t flinch. “What’s everybody ducking for?” he said. He cupped his hand to his mouth and shouted an expletive-laden taunt at the Taliban gunmen shooting from concealment on the opposite side of a field. The editors would never allow the corporal’s words to be printed here. But they amounted to this: You guys can’t shoot.

Yes, some of this was probably adrenaline and undiluted cockiness, the kind of behavior that Marines can thrive on. But this cockiness was not just attitude. It reflected a discernible truth. Much of the incoming fire was not coming close. (Later in that same fight, some of the fire did come close, as at least one sniper arrived on the Taliban side; we’ll show video of that soon). But at this point in the battle, any number of adjectives might be applied to the Taliban fighters on the far side of the open ground. They were resourceful, organized, clever, brave. In the main, however, they could not shoot.

For those of you who have served in Afghanistan, or been exposed to gunfighting there via other jobs, your input would be welcome. One of the company commanders shared his insights in an interview soon after the fighting at Marja tapered off. In the annals of the Afghan war, Afghans are supposedly crack shots, some of the best marksmen on earth. Captain Karabin, a veteran of the war in Iraq, summed up neatly a rifle company’s experience that pointed otherwise. “I used to say in Iraq that I’m only alive because Iraqis are such bad shots,” he said. “And now I’ll say it in Afghanistan. I’m only alive because the Afghans are also such bad shots.”

Story here.

——————————————————————

The Weakness of Taliban Marksmanship

April 2, 2010

By C.J. CHIVERS

Reuters Taliban fighters training in Afghanistan in 2009.

Last week, At War opened a conversation about Afghan marksmanship by publishing rough data from several dozen recent firefights between the Taliban and three Marine rifle companies in and near Marja, the location of the recent offensive in Helmand Province. The data showed that while the Taliban can be canny and brave in combat their rifle fire is often remarkably ineffective.

We plan more posts about the nature of the fighting in Afghanistan, and how this influences the experience of the war. Today this blog discusses visible factors that, individually and together, predict poor shooting results when Taliban gunmen get behind their rifles.

It’s worth noting that many survivors of multiple small-arms engagements in Afghanistan have had experiences similar to those described last week. After emerging unscathed from ambushes, including ambushes within ranges at which the Taliban’s AK-47 knock-offs should have been effective, they wonder: how did so much Taliban fire miss?

Many factors are at play. Some of you jumped ahead and submitted comments that would fit neatly on the list; thank you for the insights. Our list includes these:

1. Limited Taliban knowledge of marksmanship fundamentals.

2. A frequent reliance on automatic fire from assault rifles.

3. The poor condition of many of those rifles.

4. Old and mismatched ammunition that is also in poor condition.

5. Widespread eye problems and uncorrected vision.

6. Difficulties faced by a scattered force in organizing quality training.

There are other factors, too. But this is enough for now. Already it’s a big list.

For those who face the Taliban on patrol, the size and complexity of this list can be read as good news, because when it comes to rifle fighting, the Taliban – absent major shifts in training, equipment and logistics – are likely to remain mediocre or worse at one of the central skills of modern war. And the chance of any individual American or Afghan soldier being shot will remain very small. The flip side is that parts of the list can also be read as bad news for Western military units, because Afghan army and police ranks are dense with non-shooters, too.

Limited Appreciation of Marksmanship Fundamentals

Let’s dispense outright with talk of born marksmen. Although some people are inclined to be better shots than others, and have a knack, marksmanship itself is not a natural trait. It is an acquired skill. It requires instruction and practice. Coaching helps, too. Combat marksmanship further requires calm. Yes, the combined powers of clear vision, coordination, fitness, patience, concentration and self-discipline all play roles in how a shooter’s skill develop. So do motivation and resolve. But even a shooter with natural gifts and strong urges to fight can’t be expected to be consistently effective with a rifle with iron sights at common Afghan engagement ranges (say, 200 yards or more, often much more) without mastering the basics. These include sight picture, sight adjustment, trigger control, breathing, the use of a sling and various shooting positions that improve accuracy. (For those of you in the gun-fighting business, forgive this discussion; many readers here do not know what you know.)

Related skills are also important, the more so in Afghanistan, where distances between combatants can be long and strong winds common, especially by day, when most Taliban shooting occurs. These skills include an ability to estimate range, to account for wind as distances stretch out and a sense of how to lead moving targets — a running man, a fast-moving vehicle, a helicopter moving low over the ground. And there are many more.

We noted last week that our discussions about Taliban marksmanship rely on what can be seen and heard of incoming fire; this is because we don’t embed with the Taliban. Without being beside Taliban fighters in a firefight or attending their training classes, it can be hard to say exactly what mistakes they are making when they repeatedly miss what would seem to be easy shots, such as Marines and Afghan soldiers upright in the open at 150 yards. Two things are clear enough. First, for combatants who become expert shots, the skills that make up accurate shooting have formed into habits. Second, many Afghan insurgents do not possess the full set of these skills. This is demonstrated by the results, but also by a behavior easy to detect in firefights: they often fire an automatic, which leads to the next point.

A Frequent Reliance on Automatic Fire

Few sounds are as distinctive as those made by Kalashnikov rounds passing high overhead. The previous sentence is written that way – rounds and overhead – for a reason, because this is a common way that incoming Kalashnikov fire is heard in Afghanistan: in bursts, and high. Over and over again in ambushes and firefights, the Taliban’s gunmen fire their AK-47 knockoffs on automatic mode. The Kalashnikov series already suffers from inherent range and accuracy limitations related to its medium-power cartridges, its relatively short barrel, the short space between its rear and front sights, and the heavy mass and deliberately loose fit of the integrated bolt carrier and gas piston traveling within the receiver.

For many shooters, the limitations resulting from these design characteristics are manageable at shorter ranges and with disciplined shooting. In certain environments and conditions, including in dense vegetation where typical skirmish distances shrink, the limitations are easily overcome. Add distance between a shooter and a target, and fire a Kalashnikov on automatic, and the rifle’s weaknesses can emerge starkly. There are reasons for this. One is perceptible to people who are shot at but not struck. When fired on automatic, the weapon’s muzzle rises. Bullets start to climb. At very short ranges, a round from a climbing muzzle might still hit a man. At longer ranges, which are common in arid Afghanistan, the chances of a hit decline sharply. Rounds travel over heads.

For decades, those who have trained Afghan fighters have cajoled, preached and drilled the importance of firing on semiautomatic mode (read: one shot for each trigger pull) for most situations. A Marine lieutenant colonel I served with in the 1980s and 1990s had been previously assigned to Pakistan to train anti-Soviet mujahedeen. His accounts of Afghan and foreign fighters who were impervious to instruction on the importance of single-shot fire would seem to describe many insurgents in the field in Afghanistan today.

Poor Condition of Rifles

While Taliban fighters commonly use Kalashnikov rifles, other firearms are in the mix, including PK machine guns and sometimes Lee-Enfield rifles. After one skirmish in Marja, Kilo Company, Third Battalion, Sixth Marines captured a single-shot 12-gauge shotgun with a collapsible stock and an assortment of buckshot rounds, in addition to two Kalashnikovs. The shotgun was notable not just because it was a battlefield novelty, but also because it was in excellent condition.

The weapons captured by Kilo Company were of types well regarded for reliability. But reliability and accuracy are different things, and these rifles pointed to another factor influencing Taliban marksmanship. Look below at two weapons that the company’s First Platoon collected during a long, rolling gunfight on another day. Their condition assured that they could not be fired with optimal accuracy.

C.J. Chivers

The problem with the first rifle is easy to spot: it is missing its wooden stock. While this makes the weapon more readily concealable, it also makes it almost impossible for a shooter to hold steady while firing. A shooter who tried firing that rifle from his right shoulder would probably reconsider quickly, as the exposed and pointed base of the receiver would bruise his shoulder muscle. One likely way to fire this weapon would be to hold it away from the body while pulling the trigger.

C.J. Chivers

That is not a preferred shooting position. At short ranges this rifle could still be nasty. It is more than ready for crime. But for a complex firefight at typical ranges against a conventional Western infantry unit? Beyond providing suppressive fire and making noise, it would not be of much use.

The problem with the second rifle is more subtle but still obvious – one of the original screws that affixed the wooden stock to the rifle’s receiver is missing. Its absence allows for wobble. Wobble assures inaccuracy.

Mismatched, Old or Corroding Ammunition

A post here in January discussed the mixed sources of Taliban rifle ammunition evident in captured rifle magazines.

In February, Kilo Company captured several Taliban chest rigs, which together held many more Kalashnikov magazines. The company allowed an inventory of all of this ammunition and an examination of its condition and head stamps, which usually tell where and when a round was manufactured. The inventory showed that Taliban magazines contained a hodgepodge of old ammunition and rounds of mixed provenance, along with ammunition identical to what had been issued to Afghan government forces.

The post in January noted that this blog would discuss how mixed ammunition might undermine accuracy. Here’s the short course. Rifle cartridges that appear to be identical but are made in different factories, nations and decades can have different characteristics that affect a bullet’s flight. Different propellants, for example, change muzzle velocities and therefore change a bullet’s trajectory. Moreover, as ammunition ages, it can degrade, especially when exposed to moisture over time and to extremes in temperature. Over many years, the effects of heat cycling – the ups and downs of ammunition temperatures between night and day, and the more extreme temperature swings between winter and summer – accelerate decay and can undermine consistent ballistic performance. And when ballistic performance becomes inconsistent, bullets aimed and fired in exactly the same way do not end up in the same places.

Units that are serious about marksmanship take their ammunition seriously. They train and adjust the sights of their rifles with the same ammunition they carry in combat. They try to store ammunition in ways that keep it clean, dry, and, if not at a stable temperature, at least within a narrower temperature swing.

The ammunition carried by Taliban fighters in Marja showed a wide range of ages and points of manufacture. Sometimes a single magazine would have more than 10 different sources. Many rounds were filthy. Others were corroded. This is not a recipe for accuracy.

Poor and Uncorrected Vision

Next on the list was a matter of public health. Many Afghans suffer from uncorrected vision problems, which have roots in factors ranging from poor childhood nutrition to the scarcity of medical care. One reader submitted a comment as thought-provoking on this theme as anything we might type. The blog defers to the reader, “Rosenkranz, Boston.”

A substantial percentage of individuals worldwide suffer from myopia, which probably is the case among the Taliban as well; in general, the developing world has limited or nonexistent prescription eyewear use, and I think it’s generous to consider Afghanistan “developing.” I doubt the Taliban’s health care coverage, such as it is, has a very generous prescription policy. Additionally, the high altitude of Afghanistan increases the likelihood of cataracts due to increased ultraviolet exposure and again, there are probably limited cataract extractions, Ray-ban or Oakley options as well. Lacking extant shopping malls replete with optical shops and sunglass kiosks, and often squinting, half-blind, and sun burned, it’s amazing that the Taliban do as well as they do.

Thank you, “Rosencranz.”

Using the iron sights on an infantry rifle requires a mix of vision-related tasks. A shooter must be able to discern both the rifle’s rear and front sights (directly in front of the shooter’s face) and also see the target (as far as several hundred yards off). Then the former must be aligned with the latter. This is difficult in ideal circumstances for lightly trained gunmen; for some people with bad vision, it might be almost impossible. Over the years many officers and noncommissioned officers who train Afghan police and soldiers have said that a significant number of Afghan recruits struggle because of their eyesight. The Taliban recruit their fighters from the same population; poor vision can be expected to be a factor in their poor riflery.

The Difficulties of Organizing Training

The Taliban are a far-flung organization, and operate in decentralized fashion. As Afghan and Western troop levels have risen, and as more drones and aircraft have been flying overhead, insurgents have effectively blended into the civilian population. The shift from being an open presence to being an underground force has consequences. The old training camps in Afghanistan long ago disappeared; as a result, opportunities to provide formal instruction to new fighters are not what they were. The Taliban claim to run camps still. That may be so. Their camps are unlikely to be as robust as the network that existed through mid-2001. Areas of Pakistan also provide training sites, but again, the drone presence makes this more difficult than before. And without ample opportunities to train, the Taliban’s rank-and-file cannot be expected to master marksmanship. It is true that war can sharpen the fighting skills of surviving combatants, and so it is likely that among the Taliban there is a core of veteran and more effective fighters. But it is also true that as a combat force is pressured, attrition constantly steals its talent. Over time, without fresh recruits who have undergone sufficient training, a fighting force’s skills, as a whole, diminish. In a long war, it is not enough just to hand out ammunition and guns. History is full of examples.

Fighting on Taliban Terms

Nothing discussed above is necessarily surprising if the Taliban are considered in context. They are an insurgent force, not a conventional outfit supported by the resources of a Western government and economy. Their state of equipment and readiness are naturally lower than those of their Western foes.

Can the Taliban correct all of the problems contributing to their poor marksmanship? To do so, they would have to develop a marksmanship curriculum and the training to support it. They would have to examine their rifles and repair or replace many of them. Ammunition would have to be standardized, and eyesight problems diagnosed and treated. These ambitions have proved hard to achieve in the Afghan National Army and for the Afghan police, both of which have been supported for nearly a decade by the Pentagon. There is little reason to expect any of it to happen. Taliban rifle shooting will almost certainly stay bad.

What does this mean? The previous post ended with a quote about poor Taliban marksmanship from Capt. Stephan P. Karabin II, who commands Charlie Company, First Battalion, Third Marines. This post will wind down with the help of one of his fellow company commanders, Capt. Thomas Grace, of the battalion’s Bravo Company. Captain Grace sent an insightful e-mail here over the weekend. His note summarized many things.

First, a fuller look at his Marines’ experience with Taliban rifle fire.

[Bravo Company] has participated in over 200 patrols and been in countless engagements over the course of six months with actual boots on the ground. We have been in over a dozen actual Troop-In-Contact (TICs) warranting Close Air Support (CAS) and priority of assets because of the severity of the contact or pending contact. The only weapons systems the insurgents were effective with were machine guns, and only at suppressing our movement. We only had one instance where Marines reported single shots (possibly a “sniper” or insurgent with a long-range rifle) being effective as suppression. [Bravo Company] had no Marines struck by machine-gun or small-arms rounds, some really close calls but no hits.

Later, Captain Grace discussed how the Taliban, in spite of such unmistakably poor marksmanship skills, adapted and managed to be a relevant fighting force, and have at times elevated shoddy shooting from harassing fire into part of a complicated and lethal form of trap. Afghans who might not be able to settle into a gunfight against a patrol with superior equipment and training have learned to herd Western forces toward hidden bombs, which the military calls improvised explosive devices, or I.E.D.s.

We operated the entire deployment, on every patrol, in the horns of a dilemma. Insurgent forces would engage our forces from a distance with machine-gun fire and sporadic small arms and carefully watch our immediate actions. From day one, at the sound of the sonic pop of the round, Marines are taught to seek immediate cover and identify the source/location of the fire. Cover is almost always available in Afghanistan in the form or dirt berms, dry/filled canals and buildings. Marines tend to gravitate toward the aforementioned terrain features. So what the insurgents would do was booby-trap those areas with I.E.D.s. Whether they were pressure plates or pressure release, they were primed to detonate as Marines dove for cover. Back to the horns of a dilemma. Do I jump for the nearest cover? Run to the nearest building? Jump in the nearest canal? Do I take my chances and stand where I am and drop in place? Not necessarily the things you need to be contemplating as rounds are impacting all around you.

Three of Bravo Company’s Marines were killed, on three separate patrols, as a result of this tactic. The captain’s descriptions, and those deaths, carry an implicit message. Just because a man can’t shoot well, does not mean he is stupid or unable to fight. Western forces might be fighting an enemy with run-down equipment and comparatively primitive conventional skills. But they are fighting people, like themselves, men who think and adjust, and who can force a fight to be fought on their terms.

Again, Captain Grace:

There is no textbook countermeasure against this tactic, only constant attention to your surroundings — up, down, left and right — and over time realizing historical areas of contact and thinking about things from the enemies’ perspective.

That returns this post to its context. For the Taliban, bad shooting sometimes has proved to be good enough. For all of their shortcomings, the Taliban’s level of training and state of equipment have thus far been more than sufficient for waging a patient, low-intensity war for years, and for fighting Afghan government forces, which exhibit similar skill deficiencies. They are also more than capable of exerting influence over the Afghan civilian population, which for an insurgent is a large part of the war.

If you’ve made it this far, you deserve a fresh cup of coffee. Go get one. Check back later. It’s not just the Taliban who struggle to shoot straight. Next, At War will look at the poor shooting skills of the Afghan government troops, and provide an example of wild American rifle fire, too.

Story here.