During the recent Sudan hostage crisis, The Wall Street Journal reported that the Sudanese troops who engaged in the rescue effort were joined by a dozen armed Chinese private security contractors. While that article and coverage of the issue in the Chinese media didn’t identify where the contractors came from, there’s a strong likelihood they were drawn from the same pool of former security forces personnel that Shandong Huawei recruits from and perhaps even came from the company. Chinese sources say it was the Sudanese military that told news outlets armed Chinese contractors were participating, so it appears that Beijing wants to keep its use of private security contractors out of the public eye.

Lately I have noticed an upward trend in reporting about China and it’s private security. These three articles below help to paint that picture of what I am talking about. We have a situation where China has interests all over the world, their people are getting killed and kidnapped all over the world in higher numbers, and security situations are changing for the worse in some of these places they have set up shop in.

Not only that, but now Chinese businesses are demanding more protection and they have the money to buy it. Especially if Chinese PSC’s charge less than western companies.

This first article below talks about the company Shandong Huawei Security Group. I have never heard of them before, and I could not find a link to their website. Although I doubt I would put a link up to their site for fear of getting some virus or whatever. lol Either way, Shandong Huawei is supposed to be one of their top PSC’s.

The article also described an interesting situation going on in Iraq. As the security situation degrades and there is now a lack of western forces to keep things in check, companies like Shandong Huawei are stepping in to fill that security vacuum in order to protect companies like the China National Petroleum Corporation. Oil is of national interest to China, as it is to many countries, and PSC’s are a part of their strategy to protect those national interests.

In the quote up top it mentioned Sudan and the involvement of security contractors in the rescue of kidnapped Chinese workers. There is oil in the Sudan and China definitely has interest there. And if PSC’s are actively involved in rescue operations like this, then it is not far fetched to imagine PSC’s entering other areas of security which would border more military-like operations. Will we see a company like Shandong Huawei evolve into more of a private military company?

The other thing mentioned in this article is the strategic implications of Chinese PSC’s. Here is the quote:

There are a number of strategic implications of this rise of armed private security providers by Chinese firms. For a start, if a project is in an area unstable enough to require armed private guards, there’s a significant probability of armed encounters between security providers and potentially hostile locals. Coupled with this is the fact that given their police and military backgrounds, the contractors are likely to look and comport themselves like soldiers, and would probably be armed with similar types of weapons. There’s real potential, then, for confusion on the ground in a place like Sudan when a private contractor who looks like a soldier engages rebels or others who then mistake him for an actual member of Chinese government forces. A local whose relative was shot near a Chinese drilling site by a security guard who looks like a soldier is likely to blame Beijing, which could spark additional violence against Chinese interests in the area.

Yep. And if the local insurgency/gang/criminal elements are not getting their cut, then expect these groups to attack these Chinese ventures.

The second article below is very interesting to me because it is written by Chinese journalists and actually discusses the lack of experience that Chinese PSC’s have compared to American PSC’s. That they should ‘study’ American PSC’s….or steal trade secrets about such things. lol Either way, I thought this was cool that the Chinese have recognized the west’s expertise in this area. Check it out.

Calls for security guards from China to accompany workers posted in dangerous areas overseas have increased since kidnappings in Sudan and Egypt underscored the danger workers face as Chinese companies expand globally.

The abductions highlight the urgency to ensure the security of Chinese workers overseas, said Han Fangming, deputy director of the foreign affairs committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference National Committee, on his micro blog.

Han said that there is a need to study how private security contractors in the United States, such as Academi, work and “when the time is right, the government might allow qualified companies” to establish such services…. Another factor to consider is how prepared the security services are to handle dangerous situations.

“I think security guards in China are far from the level of private security contractors like Academi in the US,” Fu said.

Yep. Private security contractors in the US, and our western partners, have all learned many hard lessons over ten years of warfare. If China plans on allowing PSC’s to do this kind of thing in war zones, then yes, they will be looking to all and any lessons learned in order to make that work. It is also a matter of Mimicry Strategy, and whatever works best, will be copied.

The final article discusses the enormity of the Chinese presence throughout the world. It also emphasizes the threat to these citizens and the upward trend of kidnappings. More kidnappings equals more ransoms. More ransoms paid equates to a creation of a kidnapping industry where individuals purposely target Chinese. That is the price China will pay if they plan on setting up shop in these dangerous parts of the world.

The dramatic rise in overseas travel and expatriate work by Chinese was punctuated by the recent kidnappings of Chinese workers in Sudan and Egypt. “Overseas Chinese protection” (haiwai gongmin baohu) has been a critical priority since deadly attacks killed 14 Chinese workers in Afghanistan and Pakistan in 2004. Between 2006 and 2010, 6,000 Chinese citizens were evacuated to China from upheavals in the Solomon Islands, East Timor, Lebanon, Tonga, Chad, Thailand, Haiti and Kyrgyzstan.

But a new urgency has arisen in the past year: in 2011, China evacuated 48,000 citizens from Egypt, Libya, and Japan; 13 Chinese merchant sailors were murdered on the Mekong River in northern Thailand in October 2011; and in late January 2012, some 50 Chinese workers were kidnapped in two incidents by Sudanese rebels in South Kordofan province and by Bedouin tribesmen in the north of Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula.

The worldwide presence of Chinese citizens – and the dependencies that generates – will only continue to grow: in 2012, more than 60 million Chinese people will travel abroad, a figure up sixfold from 2000, and likely to reach 100 million in 2020. More than five million Chinese nationals work abroad, a figure sure to increase significantly in the years ahead.

That is a lot of Chinese traveling and working throughout the world! As the word gets out amongst the thugs/terrorists/rebels of the world, we will continue to see this Chinese kidnap and ransom trend increase. That means more protection work, and more hostage rescue or negotiation work for this young Chinese PSC market. So yes, I would speculate that we are witnessing the rise of the Private Security Dragon and who knows where this will lead. –Matt

Enter China’s Security Firms

February 21, 2012

By Andrew Erickson & Gabe Collins

Chinese private security companies are seeing an opportunity as the U.S. withdraws troops from Iraq and Afghanistan. But plenty of complications await them.

A security vacuum is developing around Chinese workers overseas. The recent kidnapping of 29 Chinese workers in Sudan (where another worker was shot dead during the abduction) and 25 workers in Egypt has sparked a strong reaction in China. As a result, Beijing is looking to bolster consular services and protection for Chinese citizens working and travelling overseas. On the corporate side, private analysts are urging companies to do a better job of training employees before they are sent abroad. Yet with at least 847,000 Chinese citizen workers and 16,000 companies scattered around the globe, some of them in active conflict zones such as Sudan, Iraq, and Afghanistan, key projects and their workers are likely to require more than just an expanded consular staff to keep them safe.

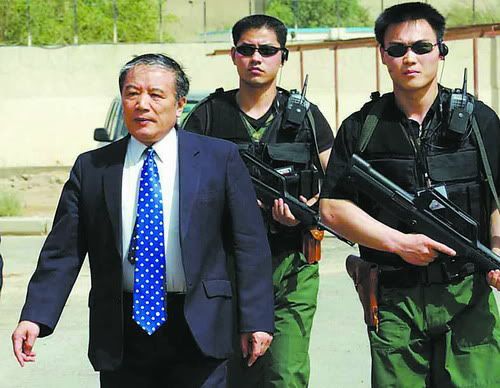

It’s with an eye on this growing danger that new Chinese private security providers see a business opportunity. Shandong Huawei Security Group appears to be a leader among Chinese security providers, which thus far have predominantly focused on the country’s robust internal market for bodyguard and protective services. Huawei provides internal services, but in October 2010, opened an “Overseas Service Center” in Beijing. The company’s statement on the center’s opening explicitly cites the withdrawal of U.S. troops from Iraq, and the potential for a security vacuum to result, as key drivers of its decision to target the Iraq market.

Chinese investors are rapidly increasing their presence in Iraq. China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC), for example, is helping to develop oil projects that will likely substantially eclipse its flagship Sudan operations in size, while Chinese construction companies are also likely to play a central role in rebuilding and improving the country’s civil and energy-related infrastructure, destroyed by years of war and neglect.

Shandong Huawei and other emerging Chinese security providers will also likely target the Afghan market. The U.S. government’s latest geological survey showed massive mineral potential in Afghanistan, with reserves of lithium, copper, cobalt, iron ore, and other minerals potentially worth as much as $1 trillion. Chinese mining and construction companies are likely to move aggressively into Afghanistan, following the example of state-owned Metallurgical Corporation of China, which is developing the massive Aynak copper deposit.

The Aynak project has benefitted from the close proximity of troops from the U.S. Army’s 10th Mountain Division, but as Washington strives to pull U.S. forces out of Afghanistan by 2014, Chinese miners will increasingly be on their own for security. As the growing number of Chinese companies and workers in Iraq and Afghanistan are forced to adapt to an environment without large U.S. military forces effectively providing a shield for their operations, the heightened security risks from insurgent attacks, banditry, and other physical threats are likely to drive them to seek new armed security providers – precisely the business opportunity that Shandong Huawei and its peers seek.

Filling the Void

The first known attempt to create a foreign-focused private security firm in China came in 2004, when a Ningbo businessman created a bodyguard firm alleged to have drawn staff from China’s special forces community and the paramilitary People’s Armed Police (PAP). In contrast, Shandong Huawei’s venture into the Iraq security market appears to be both larger-scale and focused. On its website, the company says it recruits its personnel from among retirees of special police and military units and the PAP. Huawei also specifically notes that its employees include men who have served tours in Iraq, likely former PAP who guarded China’s Ambassador to Iraq.

As far as we know, there are no other Chinese security firms publicly declaring a desire to protect Chinese businesses working abroad. Nonetheless, if Shandong Huawei’s efforts to generate business in Iraq succeed, it’s likely that more Chinese firms will target the overseas market, particularly since the domestic private security market is becoming increasingly crowded.

The global private security market is an increasingly competitive one, though, so why would a Chinese company consider hiring a firm like Shandong Huawei instead of Control Risks, G4S, or another established global security provider?

One answer is a tried and true Chinese advantage: price. Chinese sources say the cost per man for a private security guard from China range from 3,000-6,000 RMB per month ($476 to $952). Thus, a 12-man Chinese security detachment costs from $190 to $381 per day. This is comparable to the prices for local private guards in Afghanistan, but much more affordable than the rates that many Western providers would likely charge. Chinese firms would probably retain their cost advantage even if demand for experienced ex-tactical operators in China rises and wages increase.

Skill also factors in. In terms of capabilities, Shandong Huawei is currently not a “Blackwater with Chinese characteristics,” but its personnel are almost certainly very competent operators. Since the guards working for the overseas wing of most Chinese security firms would likely be drawn from personnel who had served in elite police and military units like the Snow Leopard counter-terrorism force, the general protective skill level would likely be much higher than that of local Iraqi or Afghan guards, and closer in quality to what a company would get by hiring a Western security firm. The personnel likely to form the ranks of China’s overseas private security providers won’t have the combat experience of the men working for a firm like Academi (formerly Blackwater/Xe), but they would also be conducting different types of operations, as they wouldn’t likely become offensively-oriented participants in conflicts the way Blackwater did in Iraq, for instance.

Reliability is another selling point for a company like Shandong Huawei in the eyes of Chinese companies. The track record of local forces protecting Chinese workers on overseas projects isn’t especially good. By our count, at least 43 Chinese citizens have perished since 2004 in violent attacks outside of China, including in places like Sudan where local forces are supposed to protect foreign workers. Also, with respect to future danger spots, the reputation of local security forces in Afghanistan is particularly poor. In October 2009, Taliban attackers were able to easily overpower Afghan police guards and kill 11 people at a U.N. guesthouse in Kabul, including five U.N. staff. With local forces often unreliable and influenced by complicated local and tribal politics, using a trustworthy protective service from one’s home country holds great appeal. The common language and cultural familiarity of a competent Chinese private security firm is also likely to be comforting to company managers, as it would greatly ease communication, particularly in an emergency.

Strategic Implications

Chinese armed contractors will likely appear with increasing frequency in coming crises involving Chinese citizens overseas, as they offer an option for providing Chinese companies and workers with armed protection without resorting to the more escalatory and more diplomatically risky step of deploying actual uniformed soldiers abroad to protect Chinese workers and economic assets in volatile areas.

During the recent Sudan hostage crisis, The Wall Street Journal reported that the Sudanese troops who engaged in the rescue effort were joined by a dozen armed Chinese private security contractors. While that article and coverage of the issue in the Chinese media didn’t identify where the contractors came from, there’s a strong likelihood they were drawn from the same pool of former security forces personnel that Shandong Huawei recruits from and perhaps even came from the company. Chinese sources say it was the Sudanese military that told news outlets armed Chinese contractors were participating, so it appears that Beijing wants to keep its use of private security contractors out of the public eye.

There are a number of strategic implications of this rise of armed private security providers by Chinese firms. For a start, if a project is in an area unstable enough to require armed private guards, there’s a significant probability of armed encounters between security providers and potentially hostile locals. Coupled with this is the fact that given their police and military backgrounds, the contractors are likely to look and comport themselves like soldiers, and would probably be armed with similar types of weapons. There’s real potential, then, for confusion on the ground in a place like Sudan when a private contractor who looks like a soldier engages rebels or others who then mistake him for an actual member of Chinese government forces. A local whose relative was shot near a Chinese drilling site by a security guard who looks like a soldier is likely to blame Beijing, which could spark additional violence against Chinese interests in the area.

All this raises the question of how the Chinese government would respond if a private security provider from China has a “Fallujah moment” and a large number of personnel are killed in a conflict zone, as happened to Blackwater in Iraq in 2004. In a hostile area far from home, many things can go wrong, even when a force is competent and well-prepared. Would Beijing be prepared to take punitive measures if insurgents in Sudan, Iraq, or Afghanistan managed to ambush Chinese private security guards? Would Beijing be willing to seek the help of the U.S. military for a rescue operation if Chinese contractors were under fire in an area of Iraq or Afghanistan where U.S. special forces units were in theater?

Firms who hire private security providers from China will have to find ways to manage friction with the local military and other security forces that previously protected Chinese workers and assets. Companies could end up paying twice for security – once to pay off disgruntled local commanders and then again for the actual security service from the Chinese private security provider. This could be exacerbated by the fact that the Chinese government, like Chinese companies, is perceived to be increasingly affluent. Beijing has consistently relied on paying ransoms to free hostages, while the latter, unfettered by a Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, for example, are widely perceived to engage in bribery, which is the coin of the realm in many unstable areas.

In addition, lines could be blurred if the PLA is involved in an evacuation of Chinese citizens from an active conflict zone as it did in the spring of 2011, and private armed Chinese contractors are called in to assist by private Chinese parties with urgent security needs that Beijing might not be willing to handle.

Another issue is that of the legal code of conduct that would govern the operations of private Chinese security personnel working abroad. China is a signatory to the Montreux Document, which lays out a suggested code of conduct and best practices for private military and security firms. However, the document isn’t legally binding. One possible solution to this would be for the Chinese People’s Congress to build upon the law it passed in 2011 to curtail bribery by Chinese companies working overseas and formulate a binding set of regulations for private security providers working outside Chinese borders.

More broadly, incidents involving private security contractors working outside China would also pose substantial legal and diplomatic challenges, even if the Chinese government creates laws governing the firms’ activities. For instance, we strongly suspect the Chinese response to a contractor who committed a crime in Sudan or Iraq would be to quietly whisk him back to China for legal proceedings, as opposed to risk the injustices the local judicial system might wreak upon a foreign national. This in turn would almost certainly reinforce the view that host state governments are weak and permit Chinese to enjoy extraterritoriality at the expense of locals’ desire for justice.

Finally, private security services are likely still unaffordable to the small businessmen and entrepreneurs who may venture into risky areas. As such, local groups with an ax to grind against China or who seek to put their government in a tough position could turn to targeting the private Chinese businesspeople who live outside of corporate compounds guarded by the skilled former PAP members. Under such a scenario, Beijing would have to grapple both with the diplomatic problems outlined that could result from Chinese private security firms operating in a region, as well as the pre-existing problem of private businessmen who are too small to track and effectively protect, but whose fate will nonetheless spark nationalistic reactions in China to which the government may have to respond.

Andrew Erickson is an associate professor in the Strategic Research Department at the U.S. Naval War College. Gabe Collins is the co-founder of China SignPost and a former commodity investment analyst and research fellow in the US Naval War College’s China Maritime Studies Institute.

Story here.

—————————————————————-

More consideration given to guards for overseas workers

2012-02-22

By Xu Wei

Calls for security guards from China to accompany workers posted in dangerous areas overseas have increased since kidnappings in Sudan and Egypt underscored the danger workers face as Chinese companies expand globally.

The abductions highlight the urgency to ensure the security of Chinese workers overseas, said Han Fangming, deputy director of the foreign affairs committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference National Committee, on his micro blog.

Han said that there is a need to study how private security contractors in the United States, such as Academi, work and “when the time is right, the government might allow qualified companies” to establish such services.

Han is also a board director of Sinohydro Corp, 29 of whose workers were kidnapped in Sudan on Jan 28. Three days later, 25 Chinese workers were abducted by tribesmen in Egypt.

Han said he has proposed to the Sinohydro top management team that more risk assessment of destinations must be conducted before sending workers abroad.

Xu Yuan, a road engineer at Sinohydro’s Tanzania program, said safety issues have been one of the concerns of Chinese workers at the camp since the two incidents.

“Before, we thought the only danger was of accidents at construction sites,” Xu told China Daily by e-mail, “but after the incidents, we could not help asking who can guarantee our safety if something like that happened here?”

Xu said that they have local security guards, but most of them do not seem to be reliable enough to be trusted in a crisis.

Though in Tanzania there is less chance of military attacks by rebels, Xu said, theft is common at the workers’ camp, despite the armed local security guards.

“Even if security guards from China couldn’t guarantee workers’ personal safety, they could probably make sure our property didn’t disappear so often,” Xu said.

But Chinese security companies have said they are far from being prepared for safety assignments overseas.

Fu Shen, manager of the overseas affairs branch of Beijing General Security Service, said few security companies in China offer security service overseas. Fu’s branch works with embassies and airlines in Beijing.

“It’s not all about making money. We also need to do a risk assessment of a new location when we decide to extend our service to certain places,” Fu said. “And we need to ensure the safety of security guards.”

In addition, national regulations on security guards do not cover security services overseas.

Another factor to consider is how prepared the security services are to handle dangerous situations.

“I think security guards in China are far from the level of private security contractors like Academi in the US,” Fu said.

Meanwhile, some experts said there are even more basic issues to consider before sending security guards overseas, such as legal issues.

Normally, local police and embassies are responsible for the safety of foreign nationals overseas, said Feng Xia, a professor of international law at China University of Political Science and Law.

But if a country could not fulfill that obligation, Feng said, one solution would be for the two governments to reach an agreement on the dispatching of security forces.

Feng said the act of dispatching security forces abroad would be warranted only in exceptional cases and should be done only by the government.

“Based on international law, it is inappropriate to send security guards overseas because that shows a lack of trust in the other country’s own security capacity.”

Story here.

—————————————————————

Kidnaps highlight urgent task for China

By Mathieu Duchatel and Bates Gill

Feb 8, 2012

The dramatic rise in overseas travel and expatriate work by Chinese was punctuated by the recent kidnappings of Chinese workers in Sudan and Egypt. “Overseas Chinese protection” (haiwai gongmin baohu) has been a critical priority since deadly attacks killed 14 Chinese workers in Afghanistan and Pakistan in 2004. Between 2006 and 2010, 6,000 Chinese citizens were evacuated to China from upheavals in the Solomon Islands, East Timor, Lebanon, Tonga, Chad, Thailand, Haiti and Kyrgyzstan.

But a new urgency has arisen in the past year: in 2011, China evacuated 48,000 citizens from Egypt, Libya, and Japan; 13 Chinese merchant sailors were murdered on the Mekong River in northern Thailand in October 2011; and in late January 2012, some 50 Chinese workers were kidnapped in two incidents by Sudanese rebels in South Kordofan province and by Bedouin tribesmen in the north of Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula.

The worldwide presence of Chinese citizens – and the dependencies that generates – will only continue to grow: in 2012, more than 60 million Chinese people will travel abroad, a figure up sixfold from 2000, and likely to reach 100 million in 2020. More than five million Chinese nationals work abroad, a figure sure to increase significantly in the years ahead.

‘Feeling for stones’

For now, China’s approach to this challenge follows the time-honored and pragmatic Chinese maxim of “crossing the river by feeling for stones”.

There is little alternative. The central government lacks an accurate figure of the number of overseas holders of a People’s Republic of China passport. It is estimated to be 5.5 million in 2011, dramatically up from 3.5 million in 2005. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) are said to employ 300,000 Chinese workers abroad but there are no official statistics.

Moreover, the coordination amongst the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA), the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the Ministry of Public Security (MPS), state-owned enterprises, and private businesses – problematic under most circumstances – has yet to be clarified regarding protecting citizens abroad, especially at a time when each of them are working separately to develop crisis management procedures.

The MFA is in charge of implementing consular protection. A Bureau of Consular Protection was created in May 2007 under the Department of Consular Affairs. Greater capacity will be a priority, as the department only employs 140 diplomats in Beijing and about 600 abroad.

The ministry also plays an increasing role in prevention. It disseminates security information through a website (cs.mfa.gov.cn) launched in November 2011. It has also concluded an agreement with Chinese mobile phone operators to ensure that each Chinese national traveling abroad receives a text message with basic security information (including the contact of the Chinese consulate and local police) upon arrival in a foreign country.

The Libyan operation is clearly a milestone in using the PLA to protect Chinese citizens abroad. The dispatch of a Jiangkai-II class frigate from the Gulf of Aden to the Libyan coast marked the first participation of the PLA Navy in a non-combatant evacuation operation.

Similarly, the PLA Air Force deployment of four Il-76 transport aircraft to the south of Libya, to extract Chinese citizens, was unprecedented. Less noticed was the decisive involvement of Chinese military attaches from across Europe and the Middle East who were posted at key points of evacuation across the Libyan border to help coordinate the operation.

After the October Mekong murders, the MPS directly negotiated with Myanmar, Thailand and Laos to reach the November 2011 agreement on joint river patrols. Although the MFA was involved in the negotiations, the fact that the MPS took the lead is in itself interesting – previously, the MPS’s role in foreign policy was fairly limited – and part of a larger trend of foreign policy devolution on many issues away from the MFA.

State-owned enterprises and major private corporations have important responsibilities, and not only because they sometimes employ workers in dangerous spots. Their financial clout and strong organization potentially can be a major asset in the government’s overseas protection strategy. For now, most lack standard operation procedures to prevent incidents and handle crises. Although some firms have risk assessment units, a chief security officer position has yet to be established in most of them.

Some concerns have been raised about the deployment of poorly-trained private Chinese security forces by some Chinese companies abroad, echoing similar concerns raised about private security contractors elsewhere in the world. Some experts advocate government regulation to compel SOEs to adopt overseas security budgets proportionate to the risks, but this is a cost many companies are unwilling to bear.

Past practice suggests that coordination across these actors is not standardized and tends to result only after political decisions at the highest level. For individual cases of consular protection, the MFA is firmly in the driver seat. In cases of kidnappings, severe attacks and murders, it consults with the MPS.

Larger evacuations require political endorsement from the Standing Committee of the Politburo and the Central Military Commission. While State Councilor Dai Bingguo coordinated the Egypt operation, the scale of the operation in Libya required coordination at a higher level: a task force headed by Zhang Dejiang, Politburo member, vice premier and head of the State Council Production Safety Commission.

A change for China’s foreign relations?

Looking ahead, do these developments mean big changes in Chinese foreign policy? Will Beijing further adjust its principles on sovereignty and non-intervention to take account for the safety of its citizens abroad? Will the challenge of protecting Chinese overseas lead to greater bilateral or multilateral cooperation with other major governments, such as in Europe or with the United States? Briefly put, there already are interesting changes underway, but as usual with Chinese foreign policies, these changes will likely unfold in a deliberate way and take time.

Beijing already seeks Western cooperation on these issues. For example, China relied heavily on cooperative relations with several European countries to carry out the Libyan operation. Allowing the transit through Greece of thousands of Chinese workers, some of them without a valid passport, was sensitive. In the Gulf of Aden, Western naval vessels escort Chinese merchant shipping (and Chinese escorts extend their protection to non-Chinese vessels when possible).

But additional cooperation is possible. Beijing has expressed an interest in exchanges with Europeans and Americans on evacuation operations and consular protection. The US, France and the United Kingdom have a long record of non-combatant military evacuations, and major Western companies have developed sophisticated safety policies to operate in risky locales.

But for the near-term, it is more likely that China’s priorities in this area – as in many aspects of Chinese foreign policy – will have Beijing looking inward, not outward. Setting up effective and standard procedures for protecting Chinese citizens overseas is to a great extent an institutional question regarding the distribution of costs and responsibilities between different government agencies, SOEs and private enterprises.

Further institutionalization is very likely, given leadership commitment and strong public support for a foreign policy that delivers concrete benefits “on the ground” for Chinese nationals and enterprises.

Looking ahead, the question of protecting its citizens abroad will no doubt become more pressing and complicated for Beijing. It is an inevitable risk for a globalizing China, and one that it will be grappling with for a long time to come.

Story here.

I'm curious to see if these Chinese companies will do sub-contracting work, establish a presence in the United States or partner with an American company to bid on contracts. I would definitely see a need for such a company in the Korean peninsula if North Korea decided to go to war. I would also see a need for American's that speak Mandarin or Cantonese if the demand increases.

Comment by Sam — Tuesday, March 6, 2012 @ 10:07 PM