First off, this post is not an endorsement of Ron Paul, and I purposely try to keep it apolitical here. My goal with this post was to present the ideas of the Letter of Marque, and it’s possible use in the wars dealing with drugs or terrorism. This is a tool of government, that has been used for a long time in the history of this world. It’s only in modern times that we have drifted away from these tools. In some cases, countries have made the Letter of Marque illegal, and that is too bad. But with Mexico and the US, it is still on the books and we purposely did not sign the Declaration of Paris because we wanted to retain our right to use privateers. Interesting stuff I thought, and applying this old tool to today’s problems is to me, building a steam powered snowmobile. lol And also to clarify, I am applying the concept of privateering and the Letter of Marque to land operations, as well as sea.

I also found out that the last time the US used privateers was at the beginning of World War II. The United States Navy issued a Letter of Marque to the Airship Resolute on the West Coast of the United States making it the first time the US Navy commissioned a privateer since the War of 1812. So privateers is not necessarily that old of an idea in the history of the US. Throughout the world, it is especially an old idea. Of course I have also pointed out the use of privateers during my country’s young history, and how important they were, and in this post I wanted to bring the idea up again for today’s problems.

Imagine if you would, if we issued Letters of Marque to PMC’s, with the express interest in destroying the enemies of the state and allow those PMC’s to profit from that action. That means if there is a Drug Cartel or Terrorist(s) out there that we want dead or even captured, we issue out these letters and lay out the specific terms of what that PMC could get out of the deal. Let’s say for a Drug Cartel, that PMC could capture Drug Cartel members and their property, a Prize Court could determine if they were lawfully captured and how much the PMC could take (based on the Letter of Marque), and then issue the award. That means the PMC could sell the planes, the mansions, the cars, or divvy up any cash. As for the capture of drugs, the Letter could also state exactly what is to be done with that stuff, in order for a PMC to retain the award. The draft of the Letter of Marque is extremely important, but not impossible to make. Best of all, the Letter of Marque is backed up by the US Constitution.

How about all of these bounties we issue for terrorists and drug cartels? We are trying to insert a financial incentive to the equation of capturing enemies. The next step is to just issue these letters, and I just don’t see the reasoning for not doing this? Perhaps a lawyer or any experts in Constitutional Law could explain why Letters of Marque could not be used to deal with some of our modern day issues? What is the resistance to this?

Another point I wanted to make is that Mexico has a history of using privateers as well, and they didn’t sign the Declaration of Paris either. They could set up a similar deal in their country in regards to the Letter of Marque, and implement this tool against the Drug Cartels. Or join with the US, and allow companies with this document to come in and do what they have to do. The best part about all of this, is if a company is out of control or the war is over, the issuing country could just null and void the document, or put a expiration date on it. So it would benefit the PMC to follow the Letter of Marque and not violate the agreement–or in other words, from privateer to pirate.

I could see the same thing being done in Pakistan. In both Mexico and Pakistan, you will never see US troops on the ground and that would make things really bad. Instead, the US could issue these documents to companies operating in those countries who are willing to go after the enemies of the US. Or Pakistan could issue Letters.(I don’t know if they signed any agreements forbidding it) This could also be used in for dealing with actual pirates in the Gulf of Aden–go figure? We have used this sucker before, we can use it again.

And going back to the profit of this activity, a Prize Court would have to be used to divvy up what assets these companies captured and if the actions of the company was held to the Letter. In the Letter, things like the financial assets of that organization would be fair game. Even the weapons could be sold off, or that government would pay for drugs captured as per agreement. The key component of this concept, is to make it profitable to go after these unique, and stateless enemies, yet not declare war on entire countries to get it done. If done properly, this could work, and there is certainly historical proof that this model is feasible. Actually, I owe the humble beginnings of my country to the concept. –Matt

——————————————————————

Privateering eventually died out as nations increased the sizes of their regular navies. In 1856, the maritime nations of the world signed the Declaration of Paris that outlawed privateering. Three nations–Mexico, Spain, and the United States–did not sign.

Story Here

——————————————————————

Letters of Marque and Ron Paul(Wikipedia)

Ron Paul, calling the September 11, 2001, attacks an act of “air piracy,” introduced the Marque and Reprisal Act of 2001. Letters of marque and reprisal, authorized by article I, section 8 of the Constitution, would have targeted specific terrorist suspects, instead of invoking war against a foreign state. Paul reproposed this legislation as the Marque and Reprisal Act of 2007. He voted with the majority for the original Authorization for Use of Military Force Against Terrorists in Afghanistan.

Historically, the United States issued Letters of Marque against the Barbary pirates, and commissioned privateers to attack the shipping of countries with whom the United States was at war. These letters of Marque were typically issued on a per-voyage basis, and some 1700 of them were granted by the congress during the American Revolution.

——————————————————————

Description of Privateer(Wikipedia)

A privateer was a private warship authorized by a national government to engage as a commerce raider, interrupting enemy trade. Privateers were of great benefit to a smaller naval power, or one facing an enemy dependent on trade: they disrupted commerce and hence enemy tax revenue, and forced the enemy to deploy warships to protect merchant trade. Privateering was a way of mobilizing armed ships and sailors without spending public money or commissioning naval officers. Some privateers have been particularly influential in the annals of history. The crew of a privateer might be treated as prisoners of war by the enemy country if captured. The ship itself, if a serviceable warship, might then be commissioned into regular service.

Legal framework for Privateers

Being privately owned and run, privateers did not take orders from the Naval command. The letter of marque of a privateer would typically limit activity to a specific area and to the ships of specific nations. Typically, the owners or captain would be required to post a performance bond against breaching these conditions, or they might be liable to pay damages to an injured party. In the United Kingdom, letters of marque were revoked for various offenses.

Conditions on board privateers varied widely. Some crews were treated as harshly as naval crews of the time, while others followed the comparatively relaxed rules of merchant ships. Some crews were made up of professional merchant seamen, others of pirates, debtors and convicts. Some privateers ended up becoming pirates, not just in the eyes of their enemies but also of their own nations. William Kidd, for instance, began as a legitimate British privateer but was later hanged for piracy.

——————————————————————–

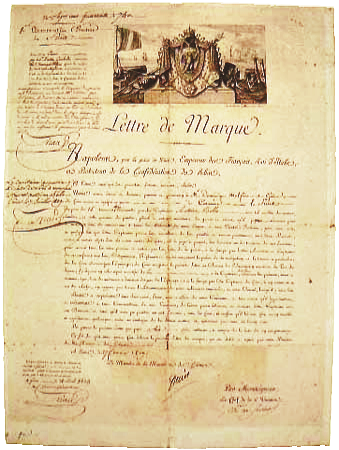

Letter of Marque(Wikipedia)

A letter of marque is an official warrant or commission from a government authorizing the designated agent to search, seize, or destroy specified assets or personnel belonging to a foreign party which has committed some offense under the laws of nations against the assets or citizens of the issuing nation, and has usually been used to authorize private parties to raid and capture merchant shipping of an enemy nation.

——————————————————————–

Is the Constitution Antiquated?

This article appeared in Ideas on Liberty, November 1999.

by Wendy McElroy

Article I of the U.S. Constitution addresses the legislative powers that are vested in—held exclusively by—the Congress. One of these powers is the right to “grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal” (Section 8, paragraph 11). Further, Section 10, paragraph 1, of this Article reads:

No State shall enter into any Treaty, Alliance, or Confederation; grant Letters of Marque and Reprisal; coin Money; emit Bills of Credit; make any Thing but gold and silver Coin a Tender in Payment of Debts; pass any Bill of Attainder, ex post facto Law, or Law impairing the Obligation of Contracts, or grant any Title of Nobility.

Paragraph 1 is an example of what many consider to be antiquated language in the Constitution, particularly with reference to the terms “Letters of Marque and Reprisal” and “Bill of Attainder.” Yet many terms considered to be antiquated not only have relevance to our modern day, but they also offer a window into the attitudes and historical events that created the United States. Only by understanding their context is it possible to understand the issues to which the Constitution speaks—then, and now.

Letters of Marque

A letter of marque—or letter of reprisal—is the means by which a government authorizes a civilian to arm a private ship in order to attack and plunder the merchant ships of an enemy nation during war. This is the meaning the term had acquired by the eighteenth century. In earlier use, it referred to the means by which a government righted a private wrong against one of its citizens. For example, if an English trader had his goods stolen in Holland and could not receive satisfaction through the Dutch legal system, the English government might grant him a letter of marque. He was then authorized to seize any Dutch ship to regain the value of the goods stolen from him. By 1700, however, the letter of marque had become an instrument of state by which government could expand its naval power during war.

Private parties who met certain requirements, such as the posting of a security bond, could arm what was called a “private ship of war” and legally plunder enemy merchant ships. Such authorized parties were called privateers by their own government and pirates by the enemy. After being adjudged as “lawful prize” by a court, the seized goods became the property of the privateer. This was his payment. Thus, the government was able to disrupt the commerce of an enemy nation without spending money.

Letters of marque assumed importance in American history as a response to the Prohibitory Act passed by Great Britain in 1775. By this Act, the rebellious colonies were stripped of protection by the English crown. Trade between the colonies and British merchants was forbidden; the seizure and plunder of American ships was encouraged. In turn, the Continental Congress issued letters of marque and reprisal that empowered colonial privateers to loot British merchant ships.

The “Instructions to the captains and commanders of private armed vessels which shall have commissions of letters of marque and reprisal,” issued by Congress on May 2, 1780, offer a sense of the restrictions placed on privateers. The primary restriction limited attacks to vessels owned by traders of the enemy nation. The private ships of war were “to pay a sacred regard to the rights of neutral powers.” The purpose of this restriction was partly to conform with international law and partly to avoid turning neutral nations into hostile ones. The privateer was ordered to “bring such ships . . . to some convenient port” where an Admiralty court could judge whether the plunder was lawful. Privateers were not to “kill or maim,—or, by torture or otherwise, cruelly, inhumanly, and contrary to common practice of civilized nations in war, treat any person or persons surprised in the ship.”

On April 16, 1856, most of the major maritime powers signed an international agreement called the Declaration Respecting Maritime Law—more popularly known as the Declaration of Paris—which abolished privateering. The United States declined to sign on the grounds that its navy was so small that letters of marque were required to bolster it during war. Without the letters the United States would be at a disadvantage versus European nations with large standing navies.

During the Spanish-American War (1898), Spain and America—neither of which was a party to the Declaration of Paris—agreed to eschew privateering. It was not until the Hague Conferences at the dawn of the twentieth century, however, that the United States officially renounced the use of letters of marque and reprisal. Thus, the term is antiquated in that it no longer applies to an activity in practice…(follow link to read more)

Story Here

A wonderful idea. And I especially like the concept of targeting the 'bad guys' rather than a whole country – put the responsibility on those whom it belongs.

Unfortunately, it will take acts of Congress (literally, pun intended) to get something like this working.

Comment by Don — Sunday, March 29, 2009 @ 7:13 AM

I'm a screenwriter in Hollywood, with more than a passing acquaintance with ocean predators, and last year, I wrote and circulated a new, original screenplay entitled "PRIVATEERS."

My story contains every element discussed here (Letters of Marque, Ron Paul, the Treaty of Paris, and Q-Boats), and it was sent to producers and studios the week before the first Somalian pirate story broke in the world news (the freighter with Russian tanks and armaments aboard was hijacked and ransomed).

Surprisingly, the script was not immediately bought, although I expect renewed interest and hope for a sale soon. Just adding this to the record, because the Internet has a way of circulating good ideas…

Carl Gottlieb

Los Angeles, CA.

Comment by Carl Gottlieb — Sunday, April 12, 2009 @ 3:23 PM