So I guess you are wondering what this might have to do with Feral Jundi? This book is a fascinating look, at what makes good people go bad. I was also interested in the author’s solution to protect people from going bad. But what was most important to me, is how I could possibly use this knowledge, as it applies to the security industry and the war effort.

I think it has everything to do with our industry, because knowing the signs and knowing the sources of what make people ‘snap’, will only help you to manage your team and your mission. It will also help you to understand your enemy.

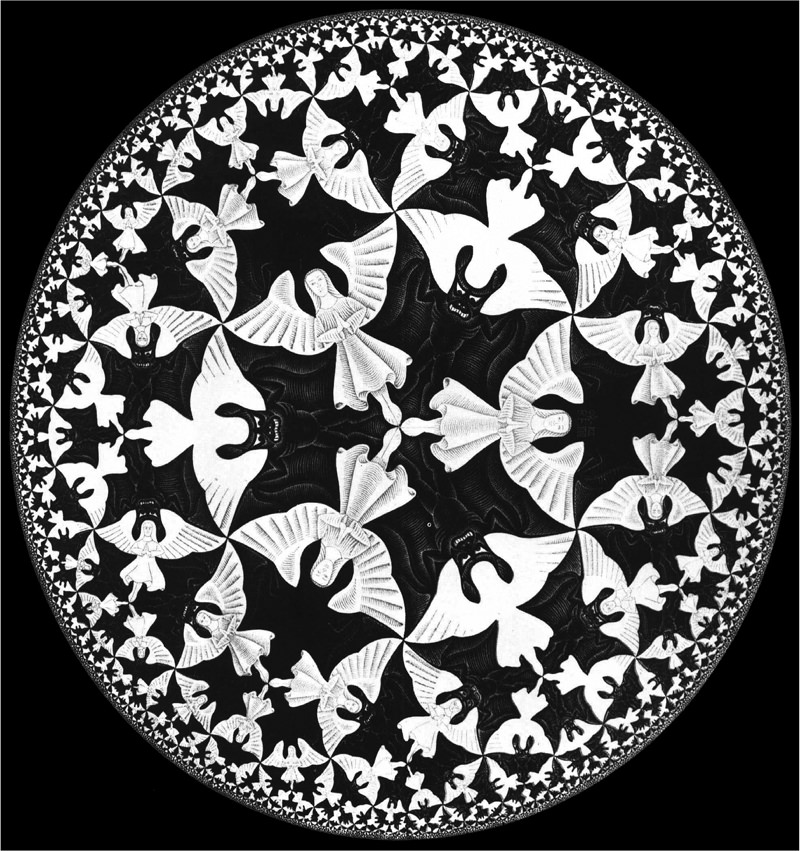

Check it out, and let me know what you think. By the way, what image did you see first in the Escher picture below? -Head Jundi

————————————————————–

The Lucifer Effect

By Philip Zimbardo

The Lucifer Effect raises a fundamental question about the nature of human nature: How is it possible for ordinary, average, even good people to become perpetrators of evil? In trying to understand unusual, or aberrant behavior, we often err in focusing exclusively on the inner determinants of genes, personality, and character, as we also tend to ignore what may be the critical catalyst for behavior change in the external Situation or in the System that creates and maintains such situations. I challenge readers to reflect on how well they really know themselves, and how much confidence they have in what they would or would not ever do when put into new behavioral settings.

This book is unique in many ways. It provides for the first time a detailed chronology of the transformations in human character that took place during the experiment I created that randomly assigned healthy, normal intelligent college students to play the roles of prison or guard in a projected 2 week-long study. I was forced to terminate the study after only 6 days because it went out of control, pacifists were becoming sadistic guards, and normal kids were breaking down emotionally. By telling that story in a new way, as my personal, first-person observation in the present tense, it is presented almost as a screen play filled with ever more amazing twists and turns as the situational forces are pitted against individual will to resist and the collective will to rebel against oppressive authority. In a sense, this study and how I am reporting its narrative, is a forerunner of reality TV, as we see ordinary people up close and personal day in and night out, becoming transformed into something truly disturbing.

The book develops this tale of agony and transformation in a crucible of human nature, doing so slowly and richly (based on typescripts of my archival videos). This extended narrative follows the opening chapter that explains the Lucifer Effect in terms of the cosmic transformation of God’s favorite angel, Lucifer, into Satan as he challenges God’s authority. We shall here be considering less dramatic transformations on a human scale that potentially can engage any of us. I lay the groundwork for the rest of the book by vivid descriptions of torture in the Inquisition, in the massacre in Rwanda, the rape of Nanking, and other venues where human nature has run amok. I also provide the initial scaffolding for how the Stanford Prison Experiment may help us make sense of corporate malfeasance, of “administrative evil,” and most particularly, the abuse and torture of prisoners by American Military Police in Iraq’s infamous Abu Ghraib prison.

After telling the story of my experiment, done with minimal psychologizing, I outline the lessons and messages from our Stanford study, along with considering ts ethics and extensions. Next, we consider the conceptual contributions and research findings from many domains that validate the assertion that situational power is stronger than we appreciate, and may come to dominate individual dispositions. I review classic and current research on: conformity, obedience to authority, role-playing, dehumanization, deindividuation and moral disengagement. I also introduce the “evil of inaction” as a new form of evil that supports those who are the perpetrators of evil, by knowing but not acting to challenge them.

Two chapters are inserted between my telling the tale of ‘the little shop of horrors’ that I created in the basement of Stanford’s psychology department and these twin chapters (12 & 13) on the social science foundations for understanding how powerful but subtle situational forces can seduce people into evil. In chapters 10 and 11, we want to know more about the broader meaning of the Stanford Prison Experiment, (SPE): What evidence was collected besides the observations the reader has looked in on? What does it mean, what are the take-home messages from this research?

A Google search for the word “experiment” uncovers a remarkable phenomenon; out of roughly 300 million results, the Stanford Prison Experiment web site ranks first!† For the word “prison,” the SPE web site ranks number two out of more than 150 million results worldwide — second only to the U.S. Federal Bureau of Prisons. That notoriety of this study is traced to examine extensions and replications of the SPE in research, the media, and recently as an art form, with critical analyses of the good and the bad directions that have been taken.

A major contribution of this book resides in its systematic application of the lessons learned from the SPE and social science research to a new understanding of the abuses at Abu Ghraib (chapter 14). I do this by integrating my psychological expertise with the special expertise I gained by being an expert witness for one of the accused Military Policemen involved in the abuses, Sgt Ivan “Chip” Frederick. I have gotten to know him well and, therefore I switched my role into that of investigative reporter as I tracked down his performance evaluations as prison guard in the States, the basis of his 9 medals and awards, corresponding with his family members and engaging psychologists to provide personality and pathology assessments of him. I have also been able to get special insight into the nature of that horrid prison from several personal contacts with military officers who have worked there. As an expert witness, I also had access to many of the independent investigations into these abuses and all of the digitally documented images of depravity that took place on Tier 1A Night Shift. So, in putting Chip Frederick on trial, I give a detailed depiction of what it was like to walk in his boots for 12-hour night shifts without a day off for 40 straight nights.

Chip got sentenced to 8 years of hard time in military prison, was dishonorably discharged, disgraced, and deprived of 22 years of retirement savings, was divorced by his wife and is now a nearly broken man. We see his transformation from good guard to bad guard to prisoner as one instance of the Lucifer Effect. However, in Chapter 15, it is my turn to shift roles again and become the prosecutor who puts the System on trial, the Military Command and the Bush Administration for their complicity in creating the System that established and maintained this and other torture-interrogation centers across many military prisons. Using the many official independent investigative reports as my sources, all of which I have read carefully, I document what they tell us about the seminal cause of the abuses in a leadership that was dysfunctional, irresponsible, conflicting or just absent.

After laying out the extent to which the abuses at Abu Ghraib pale in comparison to the more extremely violent torture and abuses in many other military sites, with testimonies of soldiers who actually took part in them, I decide that it is time for the reader to be juror and to decide whether what took place was merely the work of those 7 “bad apples,” or that of a corrupt system, a “rotten barrel,” that has sacrificed the basic human values of rule by law, honesty, and adherence to the Geneva Conventions in the cause of its obsession with the so-called “war on terror.”

Admittedly, a lot of negative stuff has been coming down in our journey into the heart and mind of darkness! But optimism is around the corner. I end Chapter 15 with an encouraging story of how an Army Colonel, a military psychologist friend of mine, took the DVD of my prison study to Abu Ghraib as a training device to teach the new guards about the corrosive effects of the power in their hands in that remote place. He was sent there to develop new procedures to prevent the recurrence of such abuses—and has done so effectively.

In our final chapter 16, the sun shines again, and lights up the dungeons we’ve inhabited for the past 15 chapters Although most people succumb to the power of situational forces, not all do. How do they resist social influence? What kinds of strategies might help the reader to become inoculated against unwanted attempts to get him or her to conform, comply, obey, and yield? I outline a 10-step generic program to build resistance to mind control strategies and tactics. Chapter 16 also presents a thought experiment to involve people in engaging in progressively greater degrees of altruistic deeds that promote civic virtue.

Given that the majority of people in my research and those of my colleagues are impacted by situational forces, it is the minority, the rare person, who resists. I consider them to be heroes. So, I end this long journey with a new understanding of what it means to be heroic. We celebrate heroes and heroism as part of new taxonomy that I have developed, which identifies 12 different types of heroes, with and criteria and exemplars. The first such exemplar takes us back to the SPE, when Christina Maslach, the young woman who forced me to terminate the experiment (and whom, I later married and is the mother of our two daughters). The second is Pvt. Joe Darby, the Abu Ghraib whistle blower who exposed the abuses and tortures taking place, thereby forcing their termination. No one has ever elaborated on the nature of heroism as I have here. Finally, we end with a novel twist to our long tale. After considering “The banality of evil” as everyman and every woman’s potential for engaging in evil deeds despite their generally moral upbringing and pro-social life style, like Adolf Eichmann, I introduce the new concept of: “The Banality of Heroism.”

Heroes come in two main casts; life-long heroes, like Nelson Mandela, Martin Luther King, Gandhi, Mother Teresa, and heroes of the moment, such as, whistle blowers, those who perform sudden acts of bravery on the battle field, or of spontaneous courage on the home front. Those heroes of the moment typically have never before done anything else that was memorable, but they responded to the call to service when they heard it. So any of us may come to act heroically by being ready to do the good thing, to help others in need when situational demands give us that rare opportunity. I end with that challenge: When the time comes for you to act the part of the hero, will you be ready for the casting call?

(As a consequence of writing this book and beginning to focus on the positive side of human nature- the heroic imagination–I have begun new research designed to understand the heroic decision at the time of taking a heroic stand against unjust authority; and also to develop a new web site devoted to celebrating heroes and heroism.)