According to the report, incomplete U.N. data shows a steady rise in the number of security contracts from 2006-2007, with the value increasing from $44 million in 2009 to $76 million in 2010, the latest data available.

The majority of contracts in 2010 – $30 million worth – were for activities by the U.N. Development Program followed by $18.5 million for U.N. peacekeeping operations and $12.2 million for U.N. refugee activities, it said.

The report said the overall value of contracts is likely to be considerably higher because data from some U.N. bodies, like the U.N. children’s agency UNICEF, is not included or incomplete.

In this post I wanted to post some statistics of interest to our industry that will help companies looking for an entry into this market. Or at least it will help companies in their research, and identifying possible niches.

Awhile back I posted a publication that discussed the UN’s increasing reliance on private security. I wanted to expand on that post a little more and identify some key statistics that report did not have, that I was able to grab elsewhere, that will further help to educate companies out there wanting to get into this sector of security.

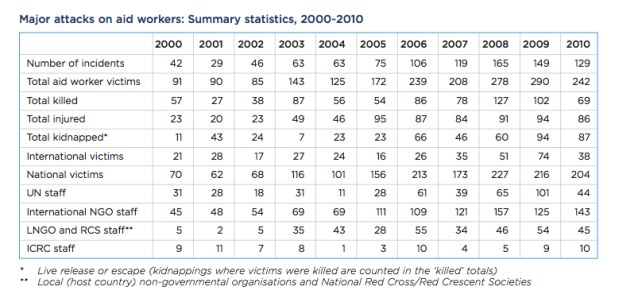

The first statistic is this one. It came from the report called ‘Aid Worker Security Report: Spotlight on security for national aid workers: Issues and perspectives (August 2011)‘ This report gives a quick run down as to the types of attacks and how many deaths there have been over the years. 2008 was the peak of deaths and was certainly a wake up call for this industry.

But these deaths also show the drive and incentive that these aid groups have when it comes to getting into these troubled spots of the world. That despite these deaths and incidents, they are still getting in there. They are driven by their donors, and if they do not produce results, then they will see a decrease in donations. Competitors in this market will get more donations if they are perceived as being ‘more effective’ in helping people.

We are also talking about millions of dollars worth of donations, and large aid organizations that have tons of folks and facilities to support with those donations. So showing worth and an ability to follow through with aid is vital if they want to continue getting donations.

Plus, groups like Aid Watchers or or Charity Watch help to further gauge the effectiveness of organizations, which help to further guide donations. These donations are also highly dependent on people having the disposable income to actually give to these causes. You can see how finicky this process can be during a downward trend in the economies of countries world wide.

There is also a lot of competition from smaller aid groups or individuals, seeking to fund their projects. In this type of competitive market for your donation, it is easy to understand why they would take the risk of sending folks into harms way to show they are more capable than the other guy.

What is also at issue is the perception of aid groups in these countries. As this applies to our industry, there is the perception that using armed security sends a negative image to the local populations. In the eyes of these clients, the security industry has an image problem.

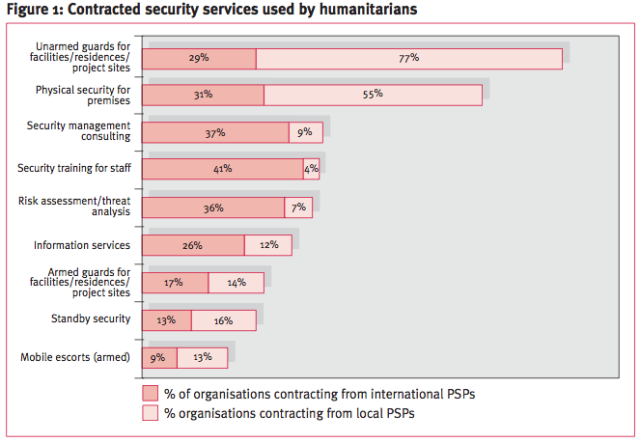

Which brings up the next statistic that I thought was interesting. What types of security services are these aid groups willing to contract, and who are they contracting with? Well, here is one graph I found from Providing Aid in Insecure Environments: Trends in violence against aid workers and the operational response (2009 Update) HPG Policy Briefs 34, April 2009.

With this graph you can see this high dependency on ‘unarmed local guards’. Which is a nice idea, but realistically in a war zone or troubled spot, unarmed guards is a horrible idea. And yet aid groups continue to depend upon this type of protection.

But for training/consulting/managing/risk assessment, international PMSC’s are still king. Which is not surprising, and I only think this will increase as aid groups continue to look at entering or holding their position in these hot zones.

Finally, I wanted to go back to the UN’s use of private security and it’s significance. The UN is a business of sorts as well. They have to show to the member countries that they are effective. If they are not able to operate in these countries and keep the peace, then they will not be able justify it’s cost and existence. So for operations that are not direct peace keeping missions, but still place staff in war zones or troubled spots, they must do all they can to hold in place and not be chased out because of incidents.

There has also been a change in philosophy at the UN, which was mentioned in this report I posted.

Change of Security Philosophy (at the UN)

During the past decade, the UN has redefined its security strategy, recognizing that the organization could no lon- ger rely on its own reputation to secure it from harm. As one high official put it, the UN can no longer count on the “strong assumption that the UN flag would protect people, protect the mission.” At the same time, the UN decided to keep a presence in dangerous conflict situations where it previously would have withdrawn. This new dual posture led the organization to rely increasingly on forceful protection measures.

The Secretary General spoke of this new approach in his 2010 report on the Safety and Security of UN Personnel. He noted that the UN was going through a “fundamental shift in mindset.” Henceforth, the organization would not be thinking about “when to leave,” but rather about “how to stay.” The UN now proposes to stay in the field even when insecurity reaches a very dangerous threshold. The Secretary General’s report, reflecting the UN’s general posture, focuses on how to “mitigate” risk, rather than considering the broader context, such as why the UN flag no longer protects and whether the UN should be present in a politically controversial role in high-risk conflict zones.

Risk outsourcing is a rarely acknowledged aspect of this security philosophy. Private contractors reduce the profile of UN-related casualties and limit the legal responsibility for damages that security operations may cause. This is similar to the posture of governments, which lessen wartime casualties among their own forces through the use of PMSCs, and thus avoid critical public pressure on the waging of war. UN officials have acknowledged in private that in situations where casualties cannot be avoided, it is better to hire contractors than to put UN staff in danger. As is the case for governments, UN use of PMSCs serves as a means to prevent public criticism of larger security policies.

Hiring the services of a PMSC can be easier as well, and can have better results than depending upon poorly trained local forces and security markets. This industry has gained experience and capability, and especially after ten plus years of war time contracting.

I also believe that the UN’s use of PMSC’s will only help private aid groups to ‘see the light’ when it comes to using security to accomplish their goals. Much like with the whole ‘armed guards on boats’ theme that I keep pounding away at in maritime security posts, I think a similar theme could be promoted for aid groups. Especially if you can associate armed security with a reduction in deaths and kidnappings, and an increase in effectiveness for all aid groups. Or if the perception of the security industry can be changed, and the image of this industry better fits into what these aid groups need.

Also, you could compare this to a ‘dance’ between our two industries. This is like a dance between two new partners with two different ideas of what good dancing is all about. As we work together in these dangerous troubled spots in the world, I believe the partnerships will only improve and get synchronized. But that only happens if our group and their groups strive to understand one another, and apply kaizen to that relationship. So hopefully this post has contributed to that understanding.

It’s a dangerous world out there, and the security industry is ready and willing to meet those challenges. –Matt

Private funding in humanitarian aid: is this trend here to stay?

By Velina Stoianova13 April 2012.

Major humanitarian crises in the past decade have prompted unprecedented amounts of private donations: the tsunami that caused widespread devastation across the Indian Ocean in December 2004 saw US$3.9 billion raised in private aid; the response to the January 2010 earthquake in Haiti generated at least US$1.2 billion in contributions from the general public; US$450 million was channelled in response to the 2010 floods in Pakistan; and at least US$578 million went to Japan following the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami. While global private support to specific large-scale emergencies is relatively easy to gauge, it remains unclear how much private money overall is out there in any given year.

GHA has released a new report today: Private funding: An emerging trend in humanitarian donorship. The report examines the upward trend in private donorship during the period 2006-2010 and the crucial role that delivery agencies play in mobilising and implementing private support to humanitarian crises. At a time when many government donor budgets are feeling the squeeze from the economic crisis, the levels of private voluntary contributions in humanitarian donorship are showing no such signs.

Nearly a quarter (24%) of the international humanitarian response for the period 2006 to 2010 came from private voluntary contributions, amounting to at least US$18 billion. US$5.8 billion was donated in 2010 alone, largely prompted by the emergency operations in Haiti and Pakistan. Private money as a share of the total humanitarian response grew from 17% in 2006 to 32% in 2010. Furthermore, importantly, private funding has remained consistent, even without the driver of mega-disasters and despite a severe global economic crisis. This trend has not escaped aid agencies, which are paying special attention to private donors. For many organisations, private money is the answer to the dilemma of how to keep responding to the growing number of aid challenges when there are limited government resources available.

Financial tracking aside, the inclusion of private voluntary contributions in the analysis of global humanitarian assistance has a significant effect on our view of the humanitarian delivery system. United Nations (UN) agencies are no longer the largest players. The report estimates that non-governmental organisations (NGOs) collectively raised US$8.7 billion in 2010; of this, US$4.9 billion came from private sources, an average of 57% of NGOs’ income over the period. NGOs have been the main channel for private support, experiencing a 70% increase in private funding from 2009-2010. The World Food Programme (WFP) remains the largest humanitarian organisation, with related income of US$3.2 billion in 2010, representing 45% of all humanitarian income to the five UN agencies analysed in the report.

If tracking total private voluntary contributions for humanitarian aid is a challenging task, gauging where this private money goes is an even more difficult undertaking. Very few organisations report their private country or sector expenditure for humanitarian aid separately from their overall funding allocations. Nevertheless, this new report shows some remarkable differences between the key recipients of private voluntary contributions and those of overall humanitarian aid channelled through delivery agencies. For instance, while Palestine is the third largest recipient of humanitarian aid (second in terms of donor governments’ allocations) for the past decade, private expenditure in the country was negligible. Afghanistan, Iraq and Pakistan – three of the key countries of interest for total official humanitarian assistance – are also very low priorities when it comes to private expenditure. However, conversely, Niger and Central African Republic, which suffer from severe funding shortfalls, are key areas for allocating private contributions.

If private support to humanitarian aid is here to stay and the system is becoming increasingly reliant on this source of funding, it is imperative that we are able to gain as clear a picture as possible of its volume, and more importantly, its use. The current lack of a dedicated tracking system for this type of funding creates an information black hole both in coordinating global humanitarian aid and evaluating the impact of private funding. The volume of funding is only one part of the picture. Not every dollar of humanitarian aid can be used in the same way, nor will each dollar have the same impact on the ground. Thus, it is critical that we are able to start systematically assessing the effectiveness of private contributions in responding to humanitarian needs and tackling vulnerability.

Story here.