This is cool. I found this older article about how asset forfeiture is benefiting the law enforcement offices of the southern states of the US. These are the states that border Mexico and have the highest probability of drug money smuggling. But I also look at this practice from an Offense Industry point of view, and also from a privateering/Letter of Marque and Reprisal point of view.

Actually, if you look at what these officers are really involved with, this is just another form of legalized piracy. lol They are arresting a criminal, and taking a prize in the form of confiscated drug money or hard assets like planes and automobiles.

And get this, the states are giving these law enforcement agencies the license or legal authority to do so. Most importantly, the federal government is supporting the act nationally. In the article below this, I posted an excerpt from the US Marshal’s page about their Asset Forfeiture Program. It is a program where local police departments can help the Department of Justice and their various ‘crack downs’ on criminals, and if there are any asset seizures during those operations, that those departments get a cut of the loot or prize.

Matter of fact, the DoJ acts like an admiralty court here, and determines the amount that the departments get and if the seizure was ‘legal’. And then when that amount is settled upon, they use an electronic funds transfer program called ‘e-share’ to give the various departments their cut. Pretty slick, and this is an excellent model on how modern day privateering could work. E-share is a technological solution to getting the ‘sailors (police) their cut of the loot’, as opposed to them selling their ‘prize tickets’ on the dock.

Now I also wanted to point out that the very thing that gives concern to NPR with their study of law enforcement asset forfeiture. Here is a quote:

What are some of the rules of asset forfeiture? Federal and state laws, in general, say that a law enforcement agency that seizes assets may not “supplant” its own budget with confiscated funds, nor should “the prospect of receiving forfeited funds … influence relative priorities of law enforcement agencies.”

NPR has found examples, mainly in the South, in which both of these things have happened.

Or basically, the fear is that law enforcement agencies will care more about going after drug money, and less about the ‘other’ duties of law enforcement. Perhaps this is why asset seizure should be a private industry game, just so police departments are not entirely focused on asset forfeiture?

The other fear with police asset forfeiture is budgetary funding for those departments. If a police department gets less tax payer funding because they are extremely successful at asset forfeiture, then now that department becomes dependent on asset forfeiture as a funding mechanism. State and city budget offices will become less inclined to fund a wealthy department, and a police department’s success in asset forfeiture could easily be their downfall. It could potentially turn a police department into more of a privateer company, and the other less profitable crime fighting activities become a secondary priority next to asset seizure.

So that is why I think asset seizure or privateering should be left in the hands of licensed companies who do not have the extra duties of basic law enforcement. And if local police departments were somehow brought into the venture of privateering as either monitors or issuing licenses, or even allowed to moonlight in privateer companies, then that is how a local department could benefit. Or some kind of tax must be paid for every asset taken in order to make this a mutually beneficial industry. You want the local cops cheering on privateer companies, not bashing them–so give them a cut, or allow them to work in those companies.

So with modern day privateering for taking drug cartel assets, the local cop shop should benefit, the state should benefit, and the federal government should benefit–all by getting a percentage of the prize. But the privateer company should benefit the most, just because they are the ones that put in the hard work for finding and seizing those assets. I think the city/state/feds should split ten percent and enjoy the reduction in crime, and the companies should get ninety percent of whatever amount. Ninety percent fits in with the percentages of yesteryear. Anything less, and the risk of taking on these criminal elements becomes too great.

The rule with offense industry is the reward must outweigh the risks for it to work and flourish. With law enforcement, they are totally enjoying the rewards of their work, and that is great. But the risk of them being too focused on this kind of activity, and not enough on the other aspects of law enforcement in their communities is equally as great. Likewise, a department is not able in some cases to totally focus all of their efforts on asset seizure, because they do have other duties. Perhaps private industry is the better choice for this kind of activity? The overall point is this kind of offense industry is an excellent study for modern day privateering, and it is all food for thought. –Matt

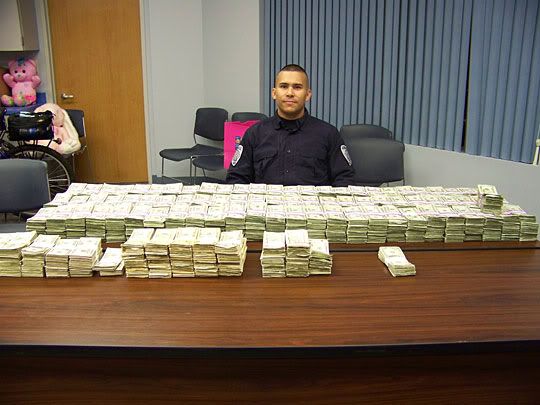

Courtesy of the Kingsville Police Department Investigator Mike Tamez of the Kingsville Police Department shows off the $1 million he discovered in a hidden compartment of a Land Rover in January 2008.

Seized Drug Assets Pad Police Budgets

by John Burnett

June 16, 2008

Every year, about $12 billion in drug profits returns to Mexico from the world’s largest narcotics market — the United States. As a tactic in the war on drugs, law enforcement pursues that drug money and is then allowed to keep a portion as an incentive to fight crime.

As a result, the amount of drug dollars flowing into local police budgets is staggering. Justice Department figures show that in the past four years alone, the amount of assets seized by local law enforcement agencies across the nation enrolled in the federal program—the vast majority of it cash—has tripled, from $567 million to $1.6 billion. And that doesn’t include tens of millions more the agencies got from state asset forfeiture programs.

In Texas, with its smuggling corridors to Mexico, public safety agencies seized more than $125 million last year.

While drug-related asset forfeitures have expanded police budgets, critics say the flow of money distorts law enforcement — that some cops have become more interested in seizing money than drugs, more interested in working southbound than northbound lanes.

“If a cop stops a car going north with a trunk full of cocaine, that makes great press coverage, makes a great photo. Then they destroy the cocaine,” says Jack Fishman, an IRS special agent for 25 years who is now a criminal defense attorney in Atlanta. “If they catch ’em going south with a suitcase full of cash, the police department just paid for its budget for the year.”

‘We have To Be Prepared’

U.S. Highway 77 follows the coastal bend of South Texas past mesquite thickets, grapefruit stands and vast historic ranches on its way to the Mexican border.

Drug agents say Highway 77 is one of the busiest smuggling corridors in the world. Think of it as a great two-way river — drugs flow north, drug money flows south. For the impoverished cities and counties situated along 77, it is like a river of gold.

On one 15-mile section that runs through Texas’ Kleberg County, the southbound lanes have become a “piggy bank,” according to the local sheriff. In the past four years, combined seizures have surpassed $7 million.

It starts with a traffic stop.

“Look at this hose. Look on this side. So that tells me somebody has messed with it. I have fingerprints right here,” says officer Mike Tamez of the Kingsville Police Department, as he inspects the engine of a gray Ford pickup truck that was headed south. He’s looking for clues to where the driver might have hidden drug money.

“Come over and look at [the] air filter housing? Look how clean these are compared to the other parts of the vehicle,” he says. After searching for 20 minutes, Tamez and the other officers crawling over the truck don’t find anything, and they send the motorists on their way.

There’s always tomorrow.

In January, Tamez — a gung-ho former Marine with a buzz cut — stopped a white Land Rover for changing lanes without using a blinker. The driver’s story was inconsistent. Then Tamez noticed fresh silicone under the rear deck. A density meter showed something bulky inside. He brought it into the shop to investigate.

“When I pulled the drill bit out there was pieces of money on it, currency. Inside the compartments we discovered 80 bundles of U.S. currency. He disavowed knowledge of everything,” Tamez says.

The bundles contained $1 million. According to the law, 80 percent of that will go to the Kingsville Police Department. So that one afternoon’s work will boost the department’s budget by 25 percent.

“Law enforcement has become a business, and where best to hit these narcotics organizations other than in the pocketbook? That’s where it’s going to hurt the most. And then to be able to turn around and use those same assets to benefit our department, that’s a win-win situation as far as we’re concerned,” says Kingsville Police Chief Ricardo Torres.

In this sleepy city of 25,000 people, with its enviable low crime rate, police officers drive high-performance Dodge Chargers and use $40,000 digital ticket writers. They’ll soon carry military-style assault rifles, and the SWAT team recently acquired sniper rifles.

When asked why the Kingsville Police Department needs sniper rifles, Torres says, “With homeland security, we all hear about where best to hit than … Middle America. This can be considered that sort of area. We have to be prepared.”

‘Addicted to Drug Money’

Federal and state rules governing asset forfeiture explicitly discourage law enforcement agencies from becoming dependent on seized drug money or allowing the prospect of those funds to influence law enforcement decisions.

There is a law enforcement culture — particularly in the South — in which police agencies have grown, in the words of one state senator from South Texas, “addicted to drug money.”

Part of the problem lies with governing bodies that count on the dirty money and, in essence, force public safety departments to freelance their own funding.

In Kleberg County, where Kingsville is the county seat, Sheriff Ed Mata drives a gleaming new police-package Ford Expedition bought with drug funds. This year, he went to his commissioners to ask for more new vehicles.

“They said, ‘Well, there ain’t no money, use your assets,’ ” he says. He says his office needs the money “to continue to operate on the magnitude we need.”

Another county agency, the Kingsville Specialized Crimes and Narcotics Task Force, survives solely on seized cash. Said one neighboring lawman, “They eat what they kill.” A review by NPR shows at least three other Texas task forces that also are funded exclusively by confiscated drug assets.

The concern here is that allowing sworn peace officers — who are entrusted with enormous powers — to make money off police work distorts criminal justice.

“We’re not going to sidestep the law and seize people’s money just for the financial gains of the department,” Tamez says. “It’s not going to happen.”

A Primer on Dirty Money

by John Burnett

June 15, 2008

Why is there so much drug money moving on U.S. highways, and what happened to money-laundering through banks?First, Mexican traffickers who’ve taken over distribution networks in the United States prefer to smuggle profits back in bulk cash. Second, it’s gotten harder to move dirty money through the financial system since a government crackdown after the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11. According to veteran DEA agent Jack Riley: “The idea of money-laundering where a bunch of people in fancy suits are sitting around a table talking about moving their drug cash to a bank in the Bahamas and then over to Switzerland — we’re not seeing that happen. What we’re seeing is, the money’s going back to Mexico the same way the drugs are — in the back of a car or in a concealed trap or in an 18-wheeler.”

How much drug money is out there, and how much of it is law enforcement confiscating?The Drug Enforcement Administration estimates $12 billion in drug profits is repatriated from the United States — the world’s largest narcotics market — back to Latin America each year. Records with the Justice Department show that state law enforcement agencies seized $1.58 billion in 2007 alone, but that doesn’t include the tens of millions of dollars that go through the state asset forfeiture programs — which are not tabulated in any central repository.

What is asset forfeiture?Asset forfeiture is the confiscation of assets associated with the commission of a crime. It can be real estate, vehicles or currency. The federal law, passed in 1986, encourages police agencies to seize drug assets as a way to deny the narcotics cartels their profits and boost the crime-fighting budgets of the agencies.

The states all passed their own asset forfeiture laws, which in many ways mimic the federal statute.

What’s the difference between criminal and civil forfeiture?In criminal forfeiture, the taking of property is usually carried out after the owner is convicted of a crime. In civil forfeiture, the government seizes the property — in this case, the currency — without ever charging the person with a crime. The government must show by a preponderance of the evidence that the money is dirty; then it’s up to the owner to prove that his cash is clean. To defend the money requires hiring a lawyer, who often charges more than the amount of the seized cash.

What are some of the rules of asset forfeiture?Federal and state laws, in general, say that a law enforcement agency that seizes assets may not “supplant” its own budget with confiscated funds, nor should “the prospect of receiving forfeited funds … influence relative priorities of law enforcement agencies.”

NPR has found examples, mainly in the South, in which both of these things have happened.

What can law enforcement agencies use seized assets for?In general, they’re supposed to be used for law enforcement purposes, such as equipment, training or first-year salaries. They are supposed to be a supplement to a police budget. Prosecutors can also use seized drug assets for the official purposes of their offices.

Story here.

—————————————————————

Asset Forfeiture Program

The Marshals Service administers the Department of Justice’s Asset Forfeiture Program by managing and disposing of properties seized and forfeited by federal law enforcement agencies and U.S. attorneys nationwide. The program has become a key part of the federal government’s efforts to combat major criminal activities.

There are three goals of the Asset Forfeiture Program: enforcing the law; improving law enforcement cooperation; and enhancing law enforcement through revenue. Asset forfeiture is a law enforcement success story, and the Marshals Service plays a vital role.

In 1984, Congress enacted the Comprehensive Crime Control Act, which gave federal prosecutors new forfeiture provisions to combat crime. Also created by this legislation was the Department of Justice Assets Forfeiture Fund (AFF). The proceeds from the sale of forfeited assets such as real property, vehicles, businesses, financial instruments, vessels, aircraft and jewelry are deposited into the AFF and are subsequently used to further law enforcement initiatives.

Moreover, under the Equitable Sharing Program, the proceeds from sales are often shared with the state and local enforcement agencies that participated in the investigation which led to the seizure of the assets. This important program enhances law enforcement cooperation between state/local agencies and federal agencies.

The asset forfeiture community consists of: The Marshals Service; U.S. Attorney’s Offices; Federal Bureau of Investigation; Drug Enforcement Administration; Department of Homeland Security, and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives.

It is important to note that the Marshals Service participates with the U.S. Attorneys Offices and the investigative agencies in pre-seizure planning — the first critical step to ensuring that sound, well-informed forfeiture decisions are made.

The role of the Marshals Service is to not only serve as custodian of seized and forfeited property but also to provide information and assist prosecutors in making informed decisions about property that is targeted for forfeiture. The Marshals Service manages and disposes of all assets seized for forfeiture by utilizing successful procedures employed by the private sector. The Marshals Service contracts with qualified vendors who minimize the amount of time an asset remains in inventory and maximize the net return to the government.

NOTE: The Marshals Service’s National Sellers List (Pub. 319P) is available from the Consumer Information Center at 1-888-878-3256 for $1.00. The same list can be downloaded or printed free of charge from the U.S. Marshals Service website by clicking here. Both sources provide the same information contained in commercially marketed publications.

Asset Forfeiture Program

E-Share Program

Welcome!??To Federal, State, and Local Law Enforcement Agencies:??I am pleased to introduce you to the United States Marshals Service (USMS) e-Share Program for disbursement of equitable sharing payments. The USMS e-Share Program is a state of the art system through which Equitable Sharing funds are transmitted to our law enforcement partners electronically.??The USMS e-Share Program is meeting the goals set by Congress in the Debt Collection Improvement Act of 1996, which requires federal agencies to comply with 21st century business standards. Equitable Sharing disbursements via Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) enable our state and local law enforcement partners to receive their equitable shares more quickly and securely.??The USMS looks forward to working with you on our joint mission to strengthen law enforcement!??Sincerely, ?Eben Morales?Assistant Director, Asset Forfeiture Division

Link to program at US Marshals here.

Good evening Matt,

Interesting stuff here. The agencies working these "letters" better have great PR as the confiscation process will be hammered in the press (I believe it may be happening now). Need stout morals on the front line to prevent this becoming a protection racket.

Keep up the great articles.

John

Comment by John — Monday, June 20, 2011 @ 7:41 PM

Absolutely. I believe the lessons learned from how these police departments conduct asset forfeiture, will be particularly helpful towards the PR strategy of a company. It should also help a government, if it wanted to go down this path. We should study what works and what does not work with these kinds of offense industries, and use those lessons to make a better 'snow mobile'.

Comment by Feral Jundi — Monday, June 20, 2011 @ 8:04 PM