This is interesting. Russia is delving into the PMSC game and looking to use Cossacks as a stepping stone for that.

I was also interested to see where the talent pool for these Cossack PMSC’s would come from? Well one clue that I came across was the forming of a Cossack party in Murmansk Oblast. This particular group was formed in the military town of Aleksandrovsk and these guys will supposedly be used for the following duties.

Among the assignments of the regional Cossack movement will be to guard the border to Norway and Finland, as well as to engage in fire fighting, street patrolling, and give military-patriotic teaching of children and young people, local Cossack representatives said.

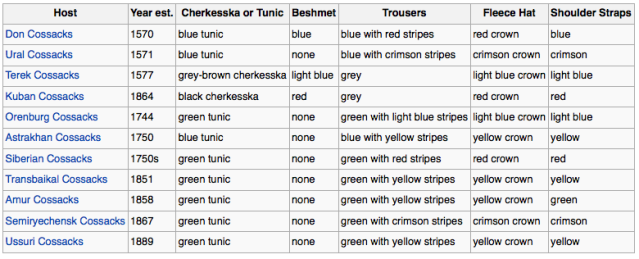

It should be noted that there are Cossack groups all over Russia, so it’s hard to say where these companies would come from. Here is a break down of those various groups (wikipedia). You could probably use the color code below to determine where Cossack PMSC’s came from for future reference.

If anyone has anything to add to this information, I am all ears. The Russian PMSC market is something that is of interest to me, but I just do not have the resources or speak the language to really make any accurate assessments about that market. I am also weary of using Russian media sources for this stuff, but that is all I have. So feedback on this would be great. –Matt

Cossack security firms to guard Russian state property

18 October, 2012

By Ramil Sitdikov

Russia will use Cossack security troops to guard military industrial objects both on its territory and abroad, says the head of the Presidential Council for Cossack issues.

The registration of the special Cossack security firms has already started, Aleksandr Beglov told reporters. Special Cossack troops can be used for providing security only to government and state-owned enterprises at federal and municipal levels, but not to private companies, added the official, who also holds the post of presidential plenipotentiary to the Central Federal District.

The Defense Ministryhas already agreed to sign contracts with Cossack companies so that they guarded some of the facilities that are now guarded by “paramilitary security structures,” Aleksandr Beglov noted.

Russia’s defense industry chief, Dmitry Rogozin, has reportedly supported the idea and said that Cossacks should provide security at various foreign-based facilities as foreign companies charge too much for such work.

Beglov added that Cossacks were planning to found and register their own Cossack Party. The founding convention is scheduled for November 24 and the leader of the new party will be elected at the same time, he said.

The official also told reporters that there were plans to set up several new associations of public organizations that would deal with problems of ethnic Russians residing abroad.

Acording to Beglov, President Putin has recently signed the strategy of the development of the Cossack movement until 2020. The document defined the ways of cooperation between Cossack organizations and state authorities of all levels. The financing of the Cossack movement will be regulated by separate programs, Beglov added.

Cossacks were a separate social group in Tsarist Russia, providing servicemen to the army and guarding the country’s borders in exchange to personal freedoms and preferences. Cossacks were monarchists and extreme nationalists, many of them were subject to repressions after the Bolshevik revolution.

Since the breakup of the Soviet Union, the Cossack movement has slowly been reviving, but it is still split and lacks state support as the government only recently started paying attention to it.

The situation is slightly different in the south of the country, especially in the Krasnodar Region – one of the territories in which Cossacks have traditionally lived. The regional governor has cooperated with Cossack troops for a long time and recently ordered that Cossacks patrolled public territory and provided security at public events.

The move drew criticism from human rights activists over fears of Cossack xenophobia, but so far no real conflicts have arisen.

Story here.

—————————————————————-

War to become a private affair

October 17, 2012

Nadezhda Sokolova

Dmitry Rogozin’s recent statement that Russia’s military-industrial commission is examining the creation of a private military sector is a sign that the market of private military services may soon come out of the shadows.

In the future, Russia’s private military companies (PMCs) could become independent domestic players, free to side with any of the “centers of power” in existence at the time.

The lack of a sound legislative framework in Russia has not posed an obstacle to the development of private military companies (PMCs), which have enjoyed a de facto presence in key conflict areas in the world for almost a decade.

For example, Antiterror-Orel (Anti-Terror Eagle, in English), which was set up by former Vnukovo Airlines employee Sergei Isakov under the auspices of Suleyman Kerimov, has been undertaking non-military operations in Iraq to protect facilities and escort cargo since 2003.

Moreover, the low competitiveness of Russian PMCs registered offshore is evidence of their narrow set of functions and, by international standards, minimal employee wages. Russian companies offer standard security services, while the largest players in the market of private military services have long since switched to multi-specialization, in which consulting and specialized training occupy key niches.

For instance, U.S.-based Academi (formerly Blackwater) focuses on training programs for U.S. military personnel, offering courses in shooting, fighting, and extreme driving at its own training base. Its main customer is the U.S. government.

PMCs in Israel, meanwhile, have secured a strong foothold in the consulting industry and, in particular, the alignment of security and intelligence systems. British PMCs specialize in risk management, logistics, and protection of financial infrastructure.

Thus, the focus of “military services” has now shifted to the developing word. It is common practice to subcontract security and escort services to smaller companies in high-risk areas, usually in unstable countries.

Even if they acquire legal status, Russian PMCs are unlikely to be successful in the market, which is currently monopolized by the U.K. and the United States. At present, Russian PMCs are simply unable to compete in the hi-tech industries, reducing their role to that of mere mercenary.

Moreover, Russia is not currently engaged in military operations abroad and does not need “rearguard” reinforcements in the form of private paramilitary structures.

The government’s decision to farm out PMCs to existing businesses clearly shows that it is more interested in two other types of commercial military structures: corporate and ethnic quasi-armies.

The former are represented by the security services of industrial companies that operate in hot spots. They already count more “security” employees than the FSB, and, in countries where Russian corporations own facilities, they essentially function in extraterritorial mode.

The legalization of military security enterprises would allow such corporations to use outsourcing in situations that require personnel with specific skills: for example, to counter attacks by pirates.

Whereas special training of corporate security services may not be commercially justified in this instance, PMCs with a niche profile could cope with the task quickly and efficiently. Furthermore, PMCs would be authorized to build up existing security capacity.

However, in addition to corporate security services that enjoy broad autonomy in overseas operations, a commercial quasi-army could also be deployed inside Russia itself. Its scope could include security in border areas in remote regions experiencing pressure from immigration; Russia’s Far East is a prime example of such a region.

Still, the commercial and tactical benefits of setting up PMCs do not alter the fact that the gradual privatization and transformation of security into an “external” service – even inside the country – is a kind of ticking time bomb. In essence, it blurs the right to commit violence, over which the state has a monopoly.

The legalization of PMCs will go hand-in-hand with an increase in illicit arms trafficking. In the future, PMCs could become independent domestic players, free to side with any of the “centers of power” in existence at the time. In fact, the situation may even stimulate another stage of neo-feudalism in Russia.

Nadezhda Sokolva is an expert at the Governance and Problem Analysis Center.

Story here.

Man, you have quite an information network, Im very envious!

Comment by CurtMiles — Thursday, October 18, 2012 @ 12:00 PM

CurtMiles Thanks CurtMiles. I have a few tricks for finding this stuff.

Comment by feraljundi — Thursday, October 18, 2012 @ 6:40 PM

It should be noted, for the record, that Cossacks, while formidable light cavalry, were historically used the by the Tsars to persecute, kill, and harass the native Jewish population of the Ukraine. There’s an ugly nativist, ultra-rightist nationalist component to these colorful troops. Didn’t the present Ukrainian government propose to “deputize” Cossacks to enforce anti-immigrant policy (read: extra-legal bullying and intimidation) against “guest workers” within the last year or so?It seems a natural choice in an increasingly xenophobic return to cold war thinking. Just sayin’

Comment by Stroopman — Thursday, October 18, 2012 @ 6:40 PM

Stroopman Yep, they do have a history.

Comment by feraljundi — Thursday, October 18, 2012 @ 6:45 PM