Conflict over land was a somewhat common occurrence in the development of the American West but was particularly prevalent during the late 1800s and early 1900s when large portions of the west were being settled by Americans for the first time. It is a period which historian Richard Maxwell Brown has called the “Western Civil War of Incorporation”.

*****

This is some fascinating history, and it reminds me a lot of the pre-Treaty of Westphalia stuff I like to delve into. During this time period in the West, famous and infamous characters started popping up. Specifically, guys like Tom Horn, Frederick Russell Burnham, or even my favorite MoH recipient, William Cody. And all of these guys were involved with some kind of warfare back then, to include range warfare.

Back then, conflict over land was very common, and cattleman did all sorts of things to protect their land and cattle. Primarily because the law back then was not very strong or capable. The west was a treacherous war zone, with Indians, grizzlies and criminals, and most had to take matters into their own hands in order to protect themselves. The law or the military could not be everywhere and at all times, and self sufficiency was key to survival. Back then, security contractors were highly sought after and very busy. Range detectives, civilian scouts, bounty hunters, contract lawman, stage coach drivers, Pony Express, Pinkertons, etc., there was all sorts of opportunities for skilled security specialists. And those that did this kind of stuff, were either veterans or adventurous types who wanted a taste of the wild west. Of course the pay was probably a draw too, because security was a premium during the development of the west.

Going back to the main theme I wanted to present. These were wars, and they were mostly fought between cattle companies trying to protect land or cattle from the other guy who was trying to gain more land and cattle. You could go back several hundred years in the history of warfare, and it would be very hard to distinguish between the wars between PMC’s or what these guys were doing in the wild west. This stuff was PMC versus PMC, and it was happening right here in America. It was also pretty brutal, as you will see below with all of the wars I posted.

I also wanted to make a quick mention of the Range Detective concept. The last known use of range detectives in the modern sense, was in Rhodesia during their war. Cattleman were paying detectives to rid their lands of cattle rustlers/insurgents there, because it was a massive problem during the conflict. Low and behold, they probably got the idea from Tom Horn and the American west’s use of Range Detectives. Hell, men like Tom were paid upwards of around $600 dollars for every rustler they killed or captured. In Rhodesia, they paid $750 Rhodesian dollars for every rustler a Range Detective was able to stop. I am sure there are other examples of individuals working in range wars in modern times, but I figured I would bring up this modern history as a documented example.

Definitely check out the Frederick Burnham story in the Pleasant Valley War I posted. I was shocked and then laughed at his luck. Not to mention his exploits in Africa which were also extremely lucky. He gets badass of the week in my opinion. lol

Now Tom Horn gets badass of the year, if we really want to get detailed. He did it all, from being a civilian scout during the Indian Wars (and finding Geronimo none the less), to working for the Pinkertons, to bounty hunting or contract law enforcement, all the way to fighting as a contract soldier in the range wars. Tom also served as a Rough Rider with Teddy Roosevelt during the Spanish-American war. He was a quite the controversial character, and to some a hero and others a criminal. He was also quoted as saying “Killing men is my specialty, I look at it as a business proposition, and I think I have a corner on the market.” He was also hung for a shooting that was deemed a murder, and that ended his prolific and intense life. Tom Horn was also portrayed by Steve McQueen in a movie called Tom Horn, and some groups even celebrate Tom Horn every year in Wyoming. Crazy.

All of it is extremely interesting, and noticing the trends back then, it seems that the guys who were good at tracking and had cut their teeth in the Indian Wars or Civil War were probably the most sought after individuals for range warfare. They knew the land, they knew how to track and kill humans, they we able to recruit others, they knew how to use weapons and they knew how to get the job done. They were fearless and skilled, and these are exactly the kind of traits that made PMC’s during the pre-Treaty of Westphalia days so valuable and sought after. Let me know what you think and check it out. –Matt

—————————————————————-

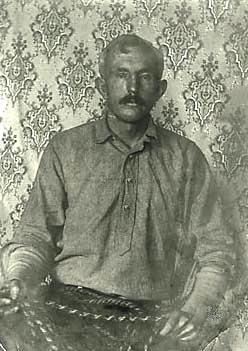

Tom Horn.

The Pleasant Valley War (also sometimes called the Tonto Basin Feud or Tonto Basin War) was an Arizona range war between two feuding families, the cattle-herding Grahams and the sheep-herding Tewksburys. Although Pleasant Valley is physically located in Gila County, Arizona, many of the events in the feud took place in Apache County, Arizona, and in Navajo County, Arizona. The feud itself lasted for almost a decade, with its most deadly incidents between 1886 and 1887, with the last known killing occurring in 1892. At one stage, outsider and known assassin Tom Horn was known to have taken part as a killer for hire, but it is unknown as to which side employed him, and both sides suffered several murders to which no suspect was ever identified. Of all the feuds that have taken place throughout American history, the Pleasant Valley War was the most costly, resulting in an almost complete annihilation of the two families involved.

Origins

During the late 1880s a number of range wars—informal undeclared violent conflicts—erupted between cattlemen and sheepmen over water rights, grazing rights, or property/border disagreements. In this case, there had been quarrels between the workhands of both factions as far back as 1882. The clashes stemmed partly from personal dislike, partly from disputed property boundaries, and partly over the Grahams’ contention that the Tewksbury sheep grazed the land clean and left little grass for cattle. In fact both families were originally cattlemen; the sheep which precipitated the escalation of hostilities may have belonged to the Daggs brothers and not to the Tewksburys at all. Regardless of the legalities, however, the Tewksburys were involved in protecting the sheep and thus in any “trouble” which might arise. Overall, perhaps 20 deaths resulted directly from the feud.

Once partisan feelings became tense and hostilities began, Frederick Russell Burnham was drawn into the conflict. He had nothing to do with the conflict, but he was dragged into it and was marked for death. Burnham hid for many days before he could escape from the valley. With the help of friends, he managed to get out of the feud district after several months during which he had a number of narrow escapes, accounts he recalls in his memoirs, Scouting on Two Continents.

The Wells Outfit

A local cattleman, Fred Wells had borrowed a lot of money in Globe, Arizona to build back his cattle herd. The Wells clan had no stake in the feud, but his creditors did. Wells was told to join their forces in driving off the opposition’s cattle or forfeit his own stock. When Wells refused, his creditors demanded immediate payment of the loans and sent two deputies to attach his cattle. Wells gathered his clan and cattle together along with a young range hand named Frederick Russell Burnham, who Wells and trained and in shooting and considered him almost a part of his family, and began driving his herd into the mountains, hotly pursued by the deputies.

It was slow going to drive the cattle into the mountains and the deputies had no trouble overtaking the Wells clan. The deputies forced the girls and the mother to halt which then set off the barking dogs. Burnham and John Wells, the son of Fred Wells and Burnham’s close friend, rushed back. Just when they arrived one of the dogs bit a deputy as he was dismounting. The deputy drew and shoot the dog, which then caused Burnham, John, and two of the girls to also draw their weapons. The dismounted deputy then fell dead, shot from a long distance by Fred Wells, and the other deputy raised his hands. The clan continued into the mountains with the captured deputy and then released him once their objectives were secure. The deputy returned to Globe and reported on the incident.

In Globe, a meeting was held to discuss the elimination of Fred and John Wells, and an “unknown gunman carrying a Remington six-shoot belt”, that is, Burnham and his Remington Model 1875 sidearm and bandolier. Private posses were raised for raiding the opposition. Killings and counter-killings became a weekly occurance. For the Wells outfit it became a sheer waste of human life in a struggle without honor or profit in another mans feud, and seemingly without end.

Frederick Russell Burnham Escapes

For Burnham, it became apparent that he had the worst of two worlds. His faction was losing and every man he killed created a new feud, a personal one, not winner take all, but winner take on all. Only 19 years old and facing a grim future as a nameless gunslinger whose only “crime” had been to stand by the his friends the Wells, Burnham went to Globe and looked up another friend, the editor of the Silver Belt newspaper. On his way to Globe he was nearly killed by George Dixon, a well-known bounty hunter and cattle rustler who found Burnham hiding in a cave. Dixon held a Colt 45 to Burnham’s head and was orderng him outside when someone outside the cave shot and killed Dixon. A White Mountain Apache indian nicknamed Coyotero had been tracking Dixon and he shot the bounty hunter though the heart just as he was capturing Burnham. Burnham immediately grabbed his Remington, moved behind a ledge, and shot Coyotero dead.

Once in Globe, Burnham contacted his friend, the Silver Belt editor, and stayed hidden in his house. With this man’s help, Burnham assumed assumed several aliases and made the difficult journey out of the Basin. He eventually arrived in Tombstone, Arizona, and stayed with friends of the Silver Belt editor. Once in Tombstone, he began to reflect on the feud: “Now my mind began to clarify. I saw that my sentimental siding with the young herder’s cause [Ed note: John Wells] was all wrong; that avenging only led to more vengeance and to even greater injustice than that suffered through the often unjustly administered laws of the land. I realized that I was in the wrong and had been for a long time, without knowing it. That was why I had suffered so in the Pinal Mountains.”

Read the rest of the story here.

——————————————————————

The Mason County War, also called the Hoodoo War (1875 – 1876) was a dispute between German-American settlers and Anglo ranchers in Mason County, Texas.

Background

The war was brought on mostly due to neither culture understanding the other, with neither making much effort to do so, in addition to political and social disagreements. However, it likely would not have resulted in violence had the area possessed a suitable and professional law enforcement element. German settlers began settling in the Mason County area early on, and by the mid-1840s they had a considerable population. However, despite a slight language barrier, the two groups at first cooperated fairly well, due to there being a considerable Indian threat. In 1860 the county’s first Sheriff, Thomas Milligan, was killed by Indians, and the settlers, both Anglo and German, banded together to hunt down the hostiles.

However, with the beginning of the American Civil War, the gaps between the two groups only got worse, as Texas voted overwhelmingly to secede, whereas in Mason County, due to the heavy German influence, the vote was overwhelming against secession. Although at that time there were no attacks in Mason County against Germans, in other parts of Texas German settlers suffered, resulting in resentment inside Mason County. The “Loyal Valley”, an area of the county, was named for the German settlers’ refusal to break away from the Union.

Following the war, although tensions were high, there was little to no trouble due to the Union Army posting troops at Fort Mason. After the army closed the fort in 1869, law enforcement was left to the local population. Many Germans held positions of authority over the Anglos, both as judges and lawmen.

Read the rest here.

——————————————————————

The Johnson County War, also known as the War on Powder River, was a range war which took place in April 1892 in Johnson County, Natrona County and Converse County in the U.S. state of Wyoming. It was a battle between small settling ranchers and larger established ranches in the Powder River Country that culminated in a lengthy shootout between local ranchers, a band of hired killers, and a sheriff’s posse, eventually requiring the intervention of the U.S. Cavalry on the orders of U.S. President Benjamin Harrison.

The events have since become a highly mythologized and symbolic story of the Wild West, and over the years variations of the storyline have come to include some of the west’s most famous historical figures and gunslingers. The storyline and its variations have served as the basis for numerous popular novels, films, and television shows.

Background

Conflict over land was a somewhat common occurrence in the development of the American West but was particularly prevalent during the late 1800s and early 1900s when large portions of the west were being settled by Americans for the first time. It is a period which historian Richard Maxwell Brown has called the “Western Civil War of Incorporation”and of which the Johnson County War was part.

In the early days in Wyoming most of the land was in the public domain, open to stock raising as open range and to homesteading. Large numbers of cattle were turned loose on the open range by large ranches.

Ranchers would hold a spring roundup where the cows and the calves belonging to each ranch were separated and the calves branded. Before the roundup, calves (especially orphan or stray calves) were sometimes surreptitiously branded. The large ranches defended against cattle rustling often by forbidding their employees from owning cattle and by lynching (or threatening to lynch) suspected rustlers. Property and use rights were usually respected among big and small ranches based on who was first to settle the land (the doctrine is known as Prior Appropriation) and the size of the herd. Nonetheless large ranching outfits would sometimes band together and use their power to monopolize large swaths of range land, preventing newcomers from settling the area.

Read the rest of the story here.

——————————————————————

The Lincoln County War was a 19th century conflict between two factions in America’s western frontier. The conflict pitted a faction of relative newcomers attempting to open a store and a bank to break a monopoly in the largest county in the United States against the owners of the monopolistic general store in Lincoln County, New Mexico, who were in business with the Territorial Attorney General, Territorial Governor and local District Attorney, both before, during, and in some cases after the conflict. A notable combatant on the side of the ranchers[clarification needed] was Billy the Kid.

The Lincoln County War Begins

In November 1876, a wealthy Englishman named John Tunstall arrived in Lincoln County, New Mexico hoping to set up a profitable cattle ranch, store, and bank in partnership with young attorney Alexander McSween and cattleman John Chisum. However, he soon discovered that Lincoln County was controlled both economically and politically by Lawrence Murphy and James Dolan, the proprietors of LG Murphy and Co., the only store in the county. LG Murphy and Co. was loaning thousands of dollars to the Territorial Governor, and the Territorial Attorney General would eventually hold the mortgage on the firm. Tunstall would also soon learn that Murphy and Dolan, who bought much of their cattle from rustlers, also had beef contracts from the United States government. These government contracts and contacts, along with their monopoly on merchandise and financing for farms and ranches, allowed Murphy, Dolan and their partner Riley to run Lincoln County as their own personal fiefdom.

Murphy and Dolan chose not to give up their monopoly lightly. In February 1878 in a sham court case that was eventually dismissed, they obtained a court order to seize all of McSween’s assets but mistakenly included all of Tunstall’s assests as McSween’s. The county sheriff, William Brady formed a posse to attach Tunstall’s remaining assets at his ranch some 70 miles from Lincoln. Since very few local citizens would join Brady’s posse, the posse contained many members of a gang of outlaws known as the Jessie Evans Gang. Murphy-Dolan also enlisted the John Kinney Gang.

On February 18, 1878, members of the Sheriff’s posse caught up to Tunstall, who was herding his last 9 horses back to Lincoln. It was later determined by Frank Warner Angel, a special investigator for the Secretary of the Interior, that Tunstall was shot in “cold blood” by Jesse Evans, William Morton, and Tom Hill. Tunstall’s murder was witnessed from a distance by several of his men, including Richard Brewer and William Henry McCarty (Billy the Kid). Tunstall’s murder is considered the event that officially marked the beginning of the Lincoln County War.

Tunstall’s cowhands and other local citizens formed a group known as the Regulators to avenge his murder since the entire criminal justice system in the Territory was controlled by allies of Murphy, Dolan & Co. While the Regulators at various times consisted of dozens of American and Mexican cowboys, the main dozen or so members were known as the “iron clad.” They included William Henry McCarty (Billy the Kid), Richard Brewer, Frank McNab, Doc Scurlock, Jim French, John Middleton, George Coe and Frank Coe, Jose Chavez y Chavez, Charlie Bowdre, Tom O’Folliard, Fred Waite, and Henry Brown.

The Regulators immediately set out to apprehend the Sheriff’s posse members who had murdered Tunstall. However after the “Regulators” were deputized and along with Constable Martinez attempted to serve the legally issued warrant on Tunstall’s murderers, Martinez and his deputies were illegally arrested, disarmed, and jailed by Sheriff Brady. After being finally released from jail the Regulators then went looking for Tunstall’s murderers. They found Buck Morton, Dick Lloyd, and Frank Baker near the Rio Peñasco. Morton surrendered after a five mile (8 km) running gunfight on the condition that Morton and his fellow deputy sheriff, Frank Baker (who, though he had no part in the Tunstall slaying, had been captured with Morton) would be returned alive to Lincoln. Although Regulator captain Richard Brewer admitted he would have preferred to kill the men, he gave the two his assurance they would be safely transported to Lincoln. However, other members of the Regulators insisted on doing away with their prisoners. Their efforts were resisted, however, by one of their own, William McCloskey, who was a friend of Morton.

On March 9, 1878, the third day of the journey back to Lincoln, in the Capitan foothills along the Blackwater Creek, McCloskey, Morton, and Baker were all killed. The Regulators claimed that Morton had murdered McCloskey, then tried to escape with Baker, forcing them to kill their two prisoners. Few believed the story, finding the idea that Morton would have killed his only friend in the group implausible. Additionally, the fact that the bodies of Morton and Baker each bore eleven bullet holes, one for each Regulator, reaffirmed suspicions that they had been deliberately murdered by their captors, and that McCloskey had lost his life for opposing it. However, other evidence seems to directly contradict Utley’s assertion and says that there were ten bullets in Morton and five in Baker. Coincidentally, on that same day Tunstall’s other two killers, Tom Hill and Jesse Evans, were also brought to justice while trying to rob a sheep drover near Tularosa, New Mexico. In the gun battle that ensued when they were discovered, Hill was killed and Evans severely wounded. While Evans was in Fort Stanton for medical treatment, he was arrested on an old federal warrant for stealing stock from an Indian reservation.

Read the rest of the story here.

I’ve been doing some ancestry research, and I had heard that my great great grandfather was a bounty hunter in Habersham/White, Georgia and had to change his name because he pissed off some people. I found this story on ancestry.com as a story that had been passed down, that he “was a deputy in Habersham County, Georgia. He killed a man over a dispute over cattle and ran to Kentucky. Once in

Kentucky, he dropped his surname and took his middle name as his last.

The gun used in the murder was passed down from his son to our time.” Do you think I would be able to find some kind of historical record on this? It would have happened around the early 1880s. I don’t know if he was some kind of officer of the law or what. This story I found just makes him sound like a murderer.

Comment by Sara — Saturday, September 14, 2013 @ 6:15 PM

@Sara Good question. I imagine you can keep digging and find tidbits here and there. Use public records and such. Another idea is to hire an expert to research this. You can also read up via some google searches on how to research and find the information you are looking for. There might be some youtube instructional videos out there as well. Good luck.

Comment by feraljundi — Sunday, September 15, 2013 @ 9:31 AM