I read these two articles by Mr. Haddick, and I took issue with a few points. First, a viable COIN/Phoenix program would not only identify the enemy within an area, but it could also collect info on potential leaders to fill the gap once that enemy is removed. And those leaders, in my view, are the natural tribal leaders that these folks would follow anyway. But really, that would be part of the mission as well, and that is to identify the best replacement leaders in a tribe or village and insure everything is in place before any action is taken.

Or maybe you don’t take any action at all and just use that information that was collected for some bigger picture stuff. My point is that we need to understand the nodes of influence in these tribes and villages, and use that information to drive the strategies in our war efforts. Kill, capture, or just watch and learn–disrupt, dismantle, or destroy.

I guess it would be nice if we could say that the government could fill in those vacancies, but in all actuality, a tribal leader would be better suited to watch over his people if some Taliban jackass was taken out of the picture. It would be nice if the government could control all of these tribes and rule over every square inch of their land, but at this time, and within the time frames we are trying to operate under, it is unrealistic. I say co-op with the tribes, and co-op with the government at the same time, and maybe some day in the future the government can actually apply some rule of law and control in these remote areas. Besides, once the government is something that is appealing to the tribes, and there is actually some benefit, then they will naturally gravitate towards that kind of thing. But with all the corruption and inability to protect anyone up in the hills, sorry, I don’t see it happening for them. There are no Lions of Panjshir that I know of in government right now.

Now the kind of program that I would like to see, is one that works with the types of tribes that support our efforts. The kind of tribes that hate the Taliban and do not want them to come back. Next is to help these tribes, like with Maj. Gant’s TET concept, to defend themselves so they are strong enough to beat back the Big T.

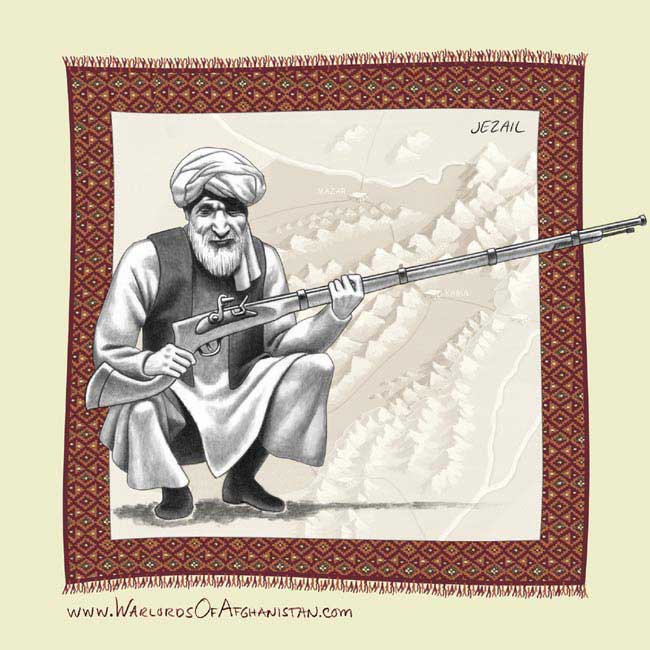

Then recruit from these tribes to form a crew that has the guts and intelligence to do the kinds of operations that would keep up the pressure on the Taliban and company well into the future. That is where the Jezailchis Scouts would come in. The JS would be the special forces of that tribe, and these scouts are the types that would be perfect for future Phoenix type programs. Especially if we wanted to send folks disguised to be Taliban, into regions that are under the Taliban death grip. You need smart and capable recruits for that kind of duty, much like the Selous Scouts were back in their war, and the Jezailchis Scouts could be the answer.

The way I envision these scouts, is that they would be fully committed to the concept of killing Taliban and practicing their deadly trade of sniping and tracking. These are the heroes and warriors of the tribes who would pride themselves on how well they shoot and maneuver in the mountains. These are the real mountain men of the region, and once this is in full swing, we could be tapping into this deadly resource for all types of missions. That is the kind of folks you would need to do really specialized types of operations, like what a Phoenix program would require. And if we were to look at how the Selous Scouts were able to assemble similar types of teams, then you would see the logic behind this and how lethal it could be. You could even recruit former Taliban for something like this, and they would be ideal candidates because of their intimate knowledge of the enemy.

That is my thoughts on the matter, and I would like to hear what you guys think? Either way, check out this paper on the Phoenix program and see if you can ‘build a snowmobile’ out of it. –Matt

——————————————————————-

The Jezailchis Scout?

Does Afghanistan need a Phoenix Program?

By Robert Haddick

July 31, 2009

The Office of the Secretary of Defense hired the RAND Corporation to study the Vietnam-era Phoenix Program and recommend whether some of the program’s controversial techniques might be useful in Afghanistan. RAND’s researchers endorsed a Phoenix-like effort for Afghanistan and in the process, attempted to dispel some of the program’s myths.

What was the Phoenix program? RAND’s relatively brief report summarizes its history: In 1967 the U.S. military command and the CIA created a program — later called Phoenix — that began as an effort to improve intelligence-sharing among a long list of U.S. and South Vietnamese agencies.

Separately but at about the same time, the CIA acted to reassert its control over some South Vietnamese counterterrorism teams it had recruited. The CIA renamed these teams Provincial Reconnaissance Units (PRUs), which later became part of the Phoenix intelligence-sharing program. Former South Vietnamese soldiers, many seeking revenge against the communist Viet Cong, made up much of the PRU membership. The CIA paid and directed these teams back to their home provinces with the mission of infiltrating the Viet Cong’s support infrastructure.

The authors believe it was the PRU portion of Phoenix that became the subject of enduring myths both good and bad. Opponents of Phoenix condemned the program as little more than an illegal assassination rampage which killed many innocent of any involvement with the Viet Cong. Proponents credited Phoenix with virtually eliminating the Viet Cong insurgency, leaving it up to the North Vietnamese army to conquer the south. The new study discounts both of these perspectives.

RAND does, however, record Phoenix as an overall success, both for its ability to gain detailed knowledge about the Viet Cong and its ability to disrupt that organization. The authors believe the U.S. counterinsurgency efforts in both Iraq and Afghanistan have suffered because the U.S. has apparently failed to aggressively recruit motivated indigenous agents to infiltrate and break up insurgent organizations.

Why wouldn’t the U.S. want to resurrect Phoenix? Infiltrating insurgent organizations would seem to be a basic counterinsurgency tactic. However, the report reminds us of one more thing: fairly or unfairly, Phoenix was very costly to the U.S. government’s reputation. The ruthlessness displayed by some unit members resulted in propaganda opportunities for opponents of the U.S. effort in Vietnam. The Vietnam War was ultimately decided on the information battlefield. That will also be the case in Afghanistan.

Story here.

*****

Does Afghanistan need the Phoenix Program? Part II

BY ROBERT HADDICK |

DECEMBER 11, 2009

A Dec. 8 Washington Post article by Griff Witte discussed the Taliban’s shadow government in Afghanistan. According to Witte, the Taliban is preparing for its return to power “by establishing an elaborate shadow government of governors, police chiefs, district administrators and judges that in many cases already has more bearing on the lives of Afghans than the real government.” In the 1960s the Viet Cong organized a similar shadow government in South Vietnam. The United States and South Vietnamese governments responded with the controversial Phoenix program, which infiltrated and crippled the Viet Cong cadre organization. President Barack Obama has tasked General Stanley McChrystal and the rest of the U.S. government to “reverse the Taliban’s momentum.” Does Afghanistan need its version of the Phoenix program?

In my July 31 column, I discussed a recent RAND Corporation report on the Phoenix program that was commissioned by the Office of the Secretary of Defense. The purpose of the report was to review the effectiveness of Phoenix’s techniques and assess whether the U.S. and Afghan governments could use those techniques effectively in Afghanistan.

Phoenix’s principal technique for attacking the Viet Cong’s organization was to recruit South Vietnamese citizens (many former soldiers) and send them back to their home provinces and villages. There they would make contact with the Viet Cong, infiltrate the organization, and collect intelligence on its structure and membership. Military and paramilitary forces would then arrest or kill the Viet Cong members. The Central Intelligence Agency, which was the lead agency for Phoenix, carefully selected the infiltrating agents based on an assessment of their motivation (often based on revenge), reliability, and adaptability.

The RAND report noted that, aside from a few exceptions, neither in Iraq nor Afghanistan has the U.S. government aggressively recruited indigenous agents to infiltrate insurgent organizations. The report offered no explanation for the neglect of this seemingly basic counterinsurgency technique.

Witte’s recent article on the Taliban’s shadow government showed why the employment of Phoenix techniques in Afghanistan might be a waste of effort. Even if such a program did reveal and destroy the Taliban shadow government, all that would remain in many parts of the country would be an empty political vacuum. According to Witte, the legitimate government has virtually no presence in many areas. And where officials and the government bureaucracy are present, their demand for bribes and inability to enforce security only seem to be alienating the population and increasing the appeal of the Taliban.

“Reversing the Taliban’s momentum” might require a ruthless Phoenix program. But that alone would be insufficient. U.S. planners are well aware of the requirement for better and cleaner Afghan governance. Delivering that in a timely manner would seem to be more difficult than eradicating the Taliban’s shadow government.

Story here.

—————————————————————-

The Phoenix Program and Contemporary Counterinsurgency

By William Rosenau, Austin Long

RAND Corporation, 2009

Conclusion

Some analysts have claimed that the lack of an insurgent shadow government in Iraq and

Afghanistan makes a Phoenix-style anti-infrastructure program in those countries both unnec-

essary and unworkable. But insurgent documents captured in Al-Anbar—at one point, Iraq’s

most violent region—describe elaborate underground bureaucratic structures with functional

elements devoted to intelligence and counterintelligence, media and propaganda, finances,

recruitment, and religious affairs. The insurgencies in Afghanistan may not be as well orga-

nized or as highly bureaucratized, but they certainly have an apparatus for financing, intelli-

gence, and recruitment that could be targeted in a selective fashion.

Applying any model from the Vietnam War in a doctrinaire fashion would be both unhelp-

ful and ahistorical. A number of analysts have claimed that contemporary insurgency is vastly

different from the Maoist people’s wars of the Cold War, in which insurgents “made revolu-

tion” in the countryside, created an alternative state, defeated the incumbent on the battlefield,

and consolidated national power.1 Although it is true that some aspects of insurgency have

changed over time—for example, the ability of armed groups to tap into regional and interna-

tional economic circuits to sustain the armed struggle is dramatically greater now—some have

endured, and differences may in fact be ones of degree rather than kind. Even during the Cold

War, the Maoist model was not the only one available to insurgents: The Gueveraist or “foco”

strategy was another well-known option. Therefore, it is hardly surprising that contemporary

insurgencies are highly variegated, manifesting themselves, organizing, and operating in a

diversity of ways. In Iraq and Afghanistan—frequently cited as examples of radically unstruc-

tured “netwar”—classic features are in evidence, including underground structures to support

operations, disseminate propaganda, and recruit militants. Effective counterinsurgency today,

as in Vietnam, calls for much more than defeating guerrillas on the battlefield: It requires the

ability to understand, map, and disrupt the insurgent infrastructure. And today, as in Viet-

nam, improved intelligence coordination and dedicated anti-infrastructure forces can play a

critical role in dismantling the subterranean “ecosystems” that sustain violent opposition.

Judged in its totality, the Vietnam War must be considered an American failure. This fail-

ure continues to resonate, and as one military historian reminds us, “it is difficult to convince

the public or policymakers that there is anything to learn from a losing effort.”2 But the failure

in Vietnam was not unmitigated. The pacification effort in general, and the Phoenix Program

in particular, met with successes.

Perhaps the most important lesson to be derived from the anti-VCI operations is the

critical requirement in any counterinsurgency to understand as fully as possible the nature

and contours of the largely invisible structures that sustain the armed opposition. Although

the United States has enjoyed considerable success in Iraq, its achievements could have come

sooner if U.S. military and intelligence officers had devoted greater resources to understanding

the inner workings of Iraq’s multiple insurgencies. For all too many Americans, the insurgen-

cies represent a black box whose inner workings—recruitment practices, sustainment activi-

ties, leadership, and decisionmaking process—remain obscured. This clandestinity was and

is partly the result of the insurgents themselves, who, like insurgents everywhere, require this

metaphorical cloak to remain viable in the face of sustained counterinsurgency operations.

But the United States has helped sustain this clandestinity, albeit unintentionally, by failing

to recognize it and strip it away. In Vietnam, most American civilians and military personnel

alike recognized the importance of prisoner interrogations as sources of crucial (and otherwise

unobtainable) information on enemy motivation and morale, strategy, tactical and operational

innovation, and intelligence operations. Unfortunately, no such comparable effort has been

made in Iraq. As the United States and its allies shift their focus to Afghanistan and weigh

counterinsurgency alternatives for that country, decisionmakers would be wise to consider how

Phoenix-style approaches might serve to pry open Taliban and Al-Qaeda black boxes.

PDF for report here.

The Brits may have already created a PRU for Helmand.

Afghan Territorial Force

Comment by Cannoneer No. 4 — Saturday, December 12, 2009 @ 10:19 AM

Interesting. It would be cool to learn what program the brits are using as a model for this ATF? Thanks and I will be looking out for more info as well.

Comment by headjundi — Saturday, December 12, 2009 @ 5:24 PM